What's The Weirdest Way to Say "River" in China?

Concerning a Rectification of (River) Names

I bet you never really thought there WAS a weird way to say “river”. Well there is. There are a lot of weird ways actually.

Do you want to get really nerdy about Chinese history and geography and rivers together with me? Yes? No? Okay, I don’t blame you…I know this will not be everyone’s cup of tea. I initially really only set out to write a small article about the new hydropower project in Tibet. I thought I would check what the name of the river means in Tibetan and accidentally got shunted into a week-long research mission to understand Chinese historical river naming conventions. Before I knew what was happening, I had written this pseudo-academic treatise on Chinese river history and I needed to share it with someone!

But hey, if you DO like geography and history this is going to be a blast, I promise.

Chinese River Names in Antiquity

You can hardly talk about China without talking about rivers. It’s a relationship that’s baked into the map of the country itself. Almost half the provinces in China have names related to water features, with rivers or other bodies of water found in the names of dozens of cities and hundreds of counties too. As a civilization built on many millennia of agriculture, China’s deep, often spiritual relationship with its waterways makes perfect sense. The story of Chinese existence, culture, and in many cases, identity itself, flow from the banks of its rivers.

When naming a river a River, there are two common words that may be used in modern Chinese: 江 (jiang1) and 河 (he2).

The longest river in China, the Yangtze, uses 江, i.e., the 长江 (Chang Jiang; “Yangtze River”). The second-longest, the Yellow, uses 河 as in 黄河 (Huang He; “Yellow River”).

It wasn’t always like that though.

The Yangtze and the Yellow are two of the four great waterways (四渎; Si Du; ) of ancient Chinese folk religion - the others being the Huai River and the (no longer existing) Ji River. From readings of ancient classics, we know that even among the four great rivers, the Yellow and Yangtze stood apart in Chinese society and culture.

In ancient times, the Yangtze River, the giant, the defining geographical feature of the south, commanded use of the proper noun “江”, while the Yellow River, the mother river, cradle of Chinese civilization, commanded use of the proper noun “河”.

That is to say, today’s modern words for “river” did not start out as generic river name suffixes as they are used today - they were proper nouns used only for referring to those specific two rivers.

At the time, the role of a generic word meaning “river” was filled by a different word, the character “水“ (shui3) with the modern definition of “water.

So, the Yangtze would have been the 江水 (jiang shui), or just its proper name 江, while the Yellow would have been the 河水 (he shui), or just its proper name 河. Other rivers like the Huai River or the Ji River would have used their own name + 水, as in the 淮水 (huai shui) or the 济水 (ji shui).

But Language is not Static

Starting in roughly the Eastern Han Dynasty, (25-220 CE) the character 河 began evolving from its origin as a proper noun to refer to the Yellow River, instead picking up a broader use as the generic suffix for river names, replacing 水 in the process.

Fun fact: the linguistic process of a proper name becoming a generic name is known as appellativization, which was a new word for me.

This gradual evolution can be seen in ancient texts from that era, most helpfully the《水经注》(Shui Jing Zhu; “Commentary on the Water Classic”), a thorough and comprehensive summary of Chinese hydrological knowledge at the time, including the source, course, and tributaries of 1252 rivers, compiled in the 6th century by the official Li Daoyuan during the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534 CE).1

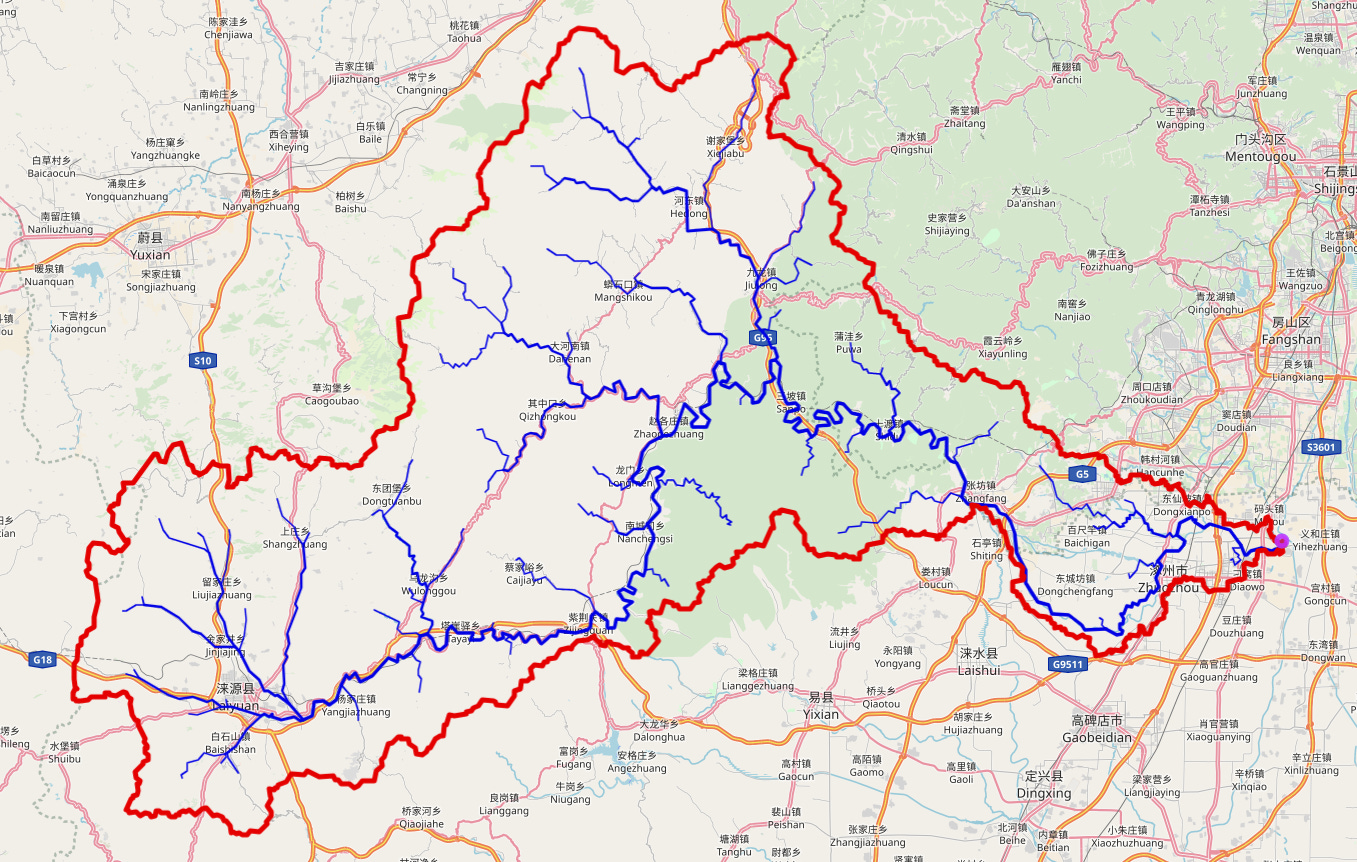

From reviewing the chapter titles, we can see the great majority of the rivers at the time were still named using a 水 as the suffix for “river”, including the Yellow River 河水 and Yangtze River 江水. However, three northern rivers using the 河 suffix had already begun to creep into the vernacular and were recorded as such, including the Juma River 巨马河 (the old name for the modern Juma River 拒马河 of Hebei and suburban Beijing). Going back 1500 years, this may be the oldest continuously-named river in China (the character changed later, but not the pronunciation).

江 Took Much Longer

江 is a different and more complex story, however. In the Commentary on the Water Classic, 江 only appears in direct reference to the Yangtze River, aside from a few cases where a 江 character happened to be within the name of a certain river, examples of which may be found elsewhere too.2 The lack of 江 used as a generic river suffix in the Commentary on the Water Classic indicates the appellativization of 江 occurred later than 河. Indeed, the earliest generalized uses of 江 do not appear for several hundred years more, in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD).

In the Tang Dynasty, the word 江 first began to get broader use to refer to some of the Yangtze’s major tributaries. Consider, for instance, a description of the Tang-era city of Baling 巴陵3 on the eastern shores of Dongting Lake, found in《元和郡县图志》 (The Gazetteer of Yuan and Jun Counties, c. 813 CE) which reads: “The city of Baling faces the mouths of three rivers: The Min River is the Western River, the Li River is the Central River, and the Xiang River is the Southern River.” “巴陵城对三江口,岷江为西江,澧江为中江,湘江为南江”.4

All three rivers named as 江 here - Min, Li, and Xiang - were understood to be upstream branches of the Yangtze (i.e., THE 江) flowing into Dongting Lake before exiting to the west as the Yangtze Proper. The Min referred to here is not the Min River of modern-day Sichuan, but a Tang-era name for of the entire section of the Yangtze River west of Dongting Lake, including the modern-day Min River, which was believed since antiquity - even by Confucius - to originate in the Min Mountains and serve as the Yangtze’s main upper trunk.5

The Min is not mentioned in the Commentary on the Water Classic, completed 300 years prior, as it was considered part of the Yangtze, but the Xiang River and Li River are, and at the time they were previously named 水, so their naming as branches of the 江 signals as an early signal of the shift for 江 to replace 水. However, the “West, Central, South” framing implies they were still being used mostly as a sort of directional modifier for the proper noun 江, like West London or South Boston. So while this is a signal of change, it’s not the definitive evolutionary proof I’d want.

More compelling evidence of the shift to the modern usage of 江, in my opinion, would be its application to a major river completely independent of the Yangtze. That doesn’t appear until a few hundred years later in the enormous Song-era imperial geography《太平寰宇记》(Taiping Huanyu Ji, 976-983 CE), which documented broad use of "江" as a suffix for southern rivers without the directional, Yangtze-centric framing. For instance, take this illustrative passage6 from Volume 157 of the Taiping Huanyu Ji, covering the Ling’nan Circuit 岭南道 (modern Guangzhou).

"As for Si Hui [四会], to the east there is the Ancient Ford Water (古津水) and the Zhen River (湞江); to the west there is the Jian Water (建水); to the north there is the Long River (龍江). Four waters (水) converge here, hence it was named for this.”

Here, we have true, decisive evidence of generic application of 江 for rivers totally unrelated to the Yangtze (these rivers are part of Guangdong’s Pearl River (珠江) water system). We also have evidence of a language in transition, with some river names still using the traditional 水 and others adopting the 江 appellativization. In its chapters on northern lands, the Taiping Huanyu Ji also provides similar evidence of the huge expansion of rivers now using 河 as a generic suffix.

How Does This Help Us Today?

Today, the wide variation of usage of 江 vs. 河 in river names nationwide may seem random and odd, particularly because they are semantically interchangeable, but there are some broad regional trends that help shape things:

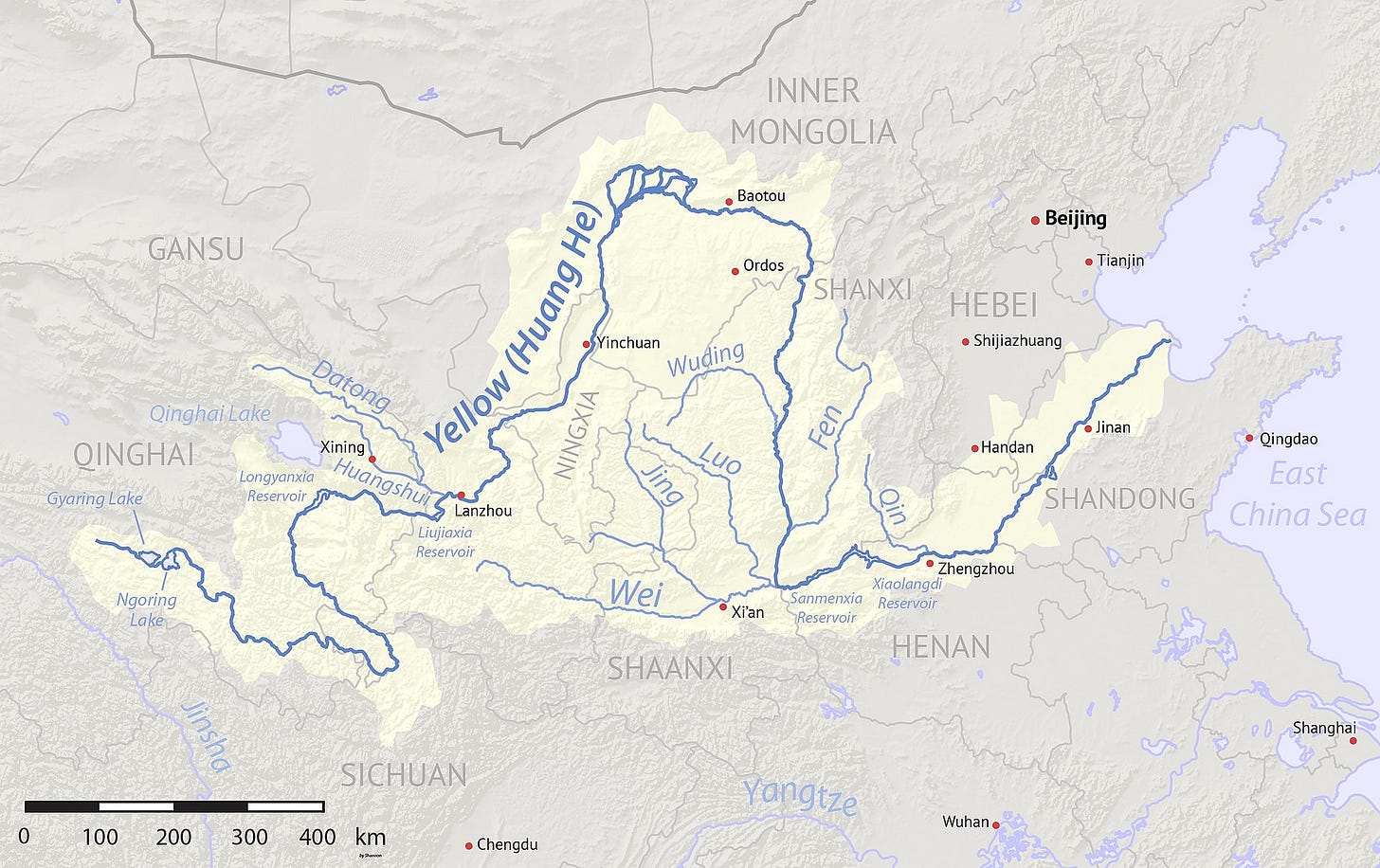

Rivers in Northern/Central China OR associated with the Yellow River drainage basin are still much more likely to use 河 in their name today, like the Wei River, Huai River, Liao River, or Fen River (渭河、淮河、辽河、汾河) .

Rivers in Southern China, OR associated with the Yangtze River drainage basin are still much more likely to use 江 in their name today, like the Xiang River, Gan River, or Pearl River (湘江、赣江、珠江).

That the South preferred to adopt 江 while the North preferred 河 was already known in the Song Dynasty. Historian Song Qi 宋祁 (998-1061) explicitly commented on it in Notes of Lord Song Jingwen, writing: “In the south, people call all waterways ‘jiang’ (江), while in the north, people call them ‘he’ (河), following their local customs.”7

Today, if I want to ask someone “what river is this?” I can ask “what 江 is this?” or “what 河 is this?” - either is no problem. But once you learn what the river’s name is, and whether it’s a 江 or a 河, you ought to remember it. If you switch around the correct “river” words used for the Yangtze and Yellow and referred to them as the 长河 or the 黄江, no one would have any idea what you’re talking about.8 So, while these two words today are interchangeable in meaning, they are fixed in actual usage.

And if you aren’t sure - just check if you’re closer to the Yellow or the Yangtze and make an educated guess!9

Modern Oddities and Exceptions to the Rule

Of course, the dominance of the 江 and 河 nomenclature and the geographic guidelines I just shared all have their limits. China is vast and its historical, cultural, and dialectal language conventions vary wildly. There are many exceptions to the rules, with oddities and regional preferences abounding. Let us examine some of them. But a few points first:

Of course, there are many words meaning “brook” or “stream”, used for bodies of flowing fresh water much smaller than rivers. I will generally try to avoid talking too much about such words like 溪 (with exceptions)、涧、涌 (in Guangdong/HK) etc., because they don’t really mean “river”.

I will also generally try to avoid talking about words specific to man-made bodies of flowing water like irrigation canals and ditches - of which there are many. This includes things like 渠、漕、浦、沟、港 (with exceptions), or 泾, etc.

With those caveats in mind, let’s get into the exceptions and oddities:

Dongbei - Major Rivers Influenced by Northern Languages

The provinces of Northeast China (Dongbei) primarily use 河 for their rivers, large and small, which is normal for the north, but notably use 江 for the Heilong River (黑龙江) and its largest tributary, the Songhua River (松花江).

As for why, the dominant theory appears to be that the languages of non-Han northern dynasties like the Khitan (Liao), Jurchen (Jin) and Manchus (Qing) had their own words for these rivers and when translating their language (e.g. Manchu “ula”) for these rivers, they consistently chose rendering as 江.10

This explanation would imply the abandonment of the 水 suffix in the Northeast occurred much later than it did farther south, which is reasonable in what had historically been a region not deeply integrated into the core Han cultural sphere. The 水 —> 江/河 transition appears to have only started in the Liao/Great Jin era (i.e. from the 10th century). Before then, rivers in that region still had names ending in 水, often transliterations of native languages.11

Guangdong - Unique Cantonese Influence

Cantonese-speaking regions of Southern China use both 江 and 河, but not interchangeably. 江 (Cantonese: gong) is generally for large and medium rivers, while 河 (Cantonese: ho) is generally for smaller rivers and urban watercourses. As far as I can tell, this is the only part of the country where a 江 is definitionally always larger than 河.

I was able to anecdotally confirm this by asking a few native Cantonese friends what they thought is the difference between 江 and 河. After thinking about it, they all confidently told me 江 is bigger than 河. When I reminded them about massive rivers in the North that use 河 like the Yellow or the Huai, they suddenly got a puzzled look. Anyway, most larger rivers and even larger tributaries in Guangdong like the Pearl River 珠江 or He River 贺江 use 江 while smaller rivers tend to use 河.

Fujian - Influenced by Min Language

Fujian uses 江 for its larger rivers, like the Min River (闽江) or Jin River (晋江) but makes somewhat unique use of a different word for the tributaries of those large rivers: 溪 (xi1). As I mentioned at the start of this section, I wouldn’t generally expect to discuss 溪 here, as it means “stream” in modern Chinese, and most of the country would only use it to describe a small waterway like a brook or creek. But Fujian almost exclusively uses 溪 to describe even very sizable tributaries like the Jian River (建溪) or the Sha River (沙溪), distinguishing it from its common usage in most of the rest of the country.

The transition away from 水 in Fujian appears to have happened around the same time as in other parts of the country (around the Song Dynasty) and the use of 溪 in modern Chinese for larger rivers, not just small mountain streams, was influenced by its definition in the Min dialect, which not restricted to just streams.

There’s also a theory that the Fujianese, as a seagoing people, were relatively unimpressed by inland rivers, even the large ones, as they all pale in scale to the ocean, and thus more likely to term them as “streams”. I don't know about this one, but it’s an amusing side explanation. Probably more folk etymology though.

Zhejiang - Stuck between Min and Wu Dialects

Zhejiang broadly uses 江 for large rivers like the Qiantang River (钱塘江) but also employs a few region-specific specialties for smaller rivers, including 溪 in southern Zhejiang, close to the Fujian border. It also sometimes uses 港 (gang3) in northern Zhejiang, which means “port” in standard Mandarin, but in the local Wu dialect preserves an old meaning of “small river”, (often man-made) related to the UNESCO-listed Lake Tai “lou-gang” 溇港 irrigation control system. I didn’t want to talk much about 港 because it’s supposed to be man-made, but I also found examples of small rivers using the 港 suffix in Zhejiang that appear to be natural rivers, so I thought I’d mention it here.

Qinghai, Tibet - Transliterations from Tibetan Language and Linguistic Redundancy

While most major rivers in Tibetan language and culture regions of Western China will generally use 河 or 江, most smaller rivers or tributaries will still use 曲 (qu1), which is the Chinese transliteration of the Tibetan word “chu” meaning “river” or “water”. For instance, the Za River (Za Qu; 杂曲) and Ngom River (Ang Qu; 昂曲) merge in Chamdo Prefecture, Tibet, where they become the Lancang River 澜沧江.12

Some large rivers in Tibet still use the traditional Tibetan word “Zangbo” for a major river, with no other suffix attached - e.g. the Za'gya Zangbo (扎加藏布; “Grey-White River”) - the largest inland river in Tibet. Others have already had the redundant 江 added to the end, such as the Yarlung Zangbo River 雅鲁藏布江, which means something like “Great Chieftain River River”.

Fun fact courtesy of a reader: When a geographic location has a redundant or repetitive name like “Great Chieftain River River”, usually because it includes multiple languages, it is known as a “tautological name.”

Inner Mongolia - Transliterations from Mongolian and Linguistic Redundancy

Many rivers in Inner Mongolia have names using both the Mongolian word for “river” - mörön (木伦) - and the Chinese word for river 河. The result is redundancy of course - or “a tautological name”. For instance, the official name of Ordos’s Ulan Mörön (“Red River” in Mongolian) is rendered as 乌兰木伦河 (Wu Lan Mu Lun He) which means “Red River River”.

Linguistic Fossils: 水 - a Bridge to Antiquity

Above, I mentioned how 河 and 江 were once solely used as the proper names for the Yellow and Yangtze respectively, while generic rivers used 水 until around the time of the Eastern Han. However, some Chinese regions continued to use 水 for their river names, centuries after other regions shifted to using 江 or 河 instead - even up to the modern day. Before I began researching for this essay, I was vaguely aware that this was still a thing, but not exactly sure where and why, so I set out to do some research. Here’s what I found:

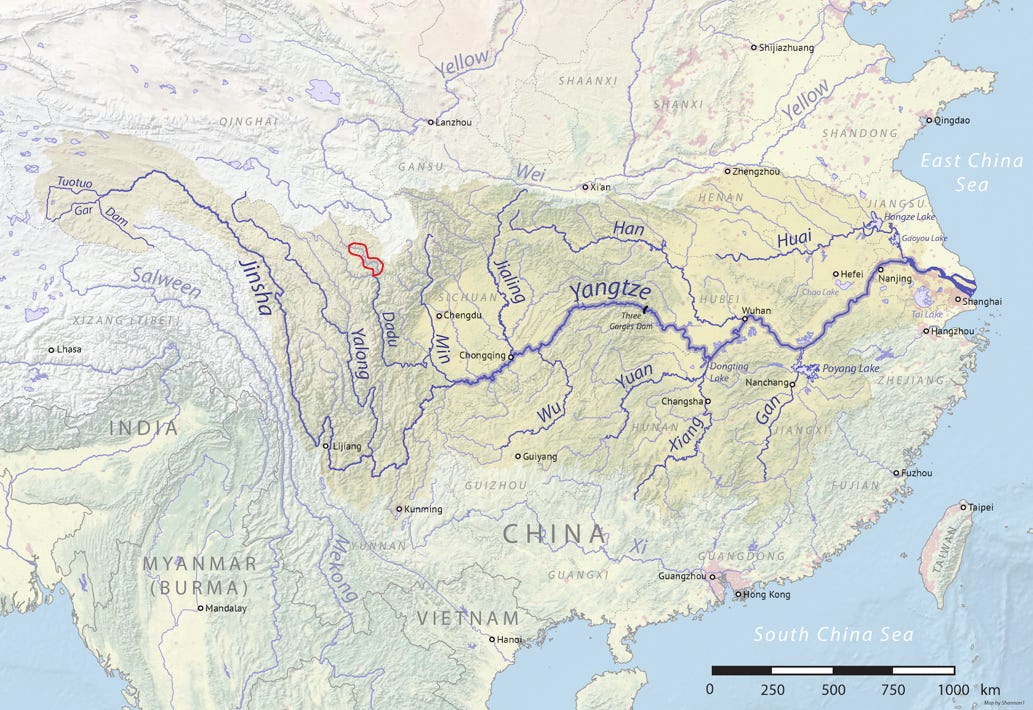

Overall, the tendency to continue using 水 is found within provinces in the drainage basin of the Yangtze River. There are few to zero 水 holdouts in the Yellow River drainage basin in Central or Northern China.13

There are some rivers commonly cited in online sources as currently using 水 in their name today for which I struggled to find practical evidence, like the Han River, the Yangtze’s longest tributary. I couldn’t find that name on any modern maps or government documents, though, so I decided to leave it out.14

I ended up concluding overall that Hunan and Jiangxi remain the greatest source of 水 holdouts - finding numerous examples in these two provinces of rivers retaining the ancient 水 suffix in their official modern names.

Hunan in particular is the 水 mother lode. In Hunan traditions, there are four rivers that stand above the rest in importance, defining the province overall (湖南四水). Those four rivers are:

Xiang River: Used to be called the 湘水, now only called the 湘江. Flows into Dongting Lake.

Yuan River: Used to be called 沅水, now only called the 沅江. Flows into Dongting Lake.

Zi River: Still called the 资水 to this day. It may also be called the 资江, but the 资水 seems much more common. Flows into Dongting Lake.

Li River:15 Still called the 澧水 to this day. Tributary of the Yuan River

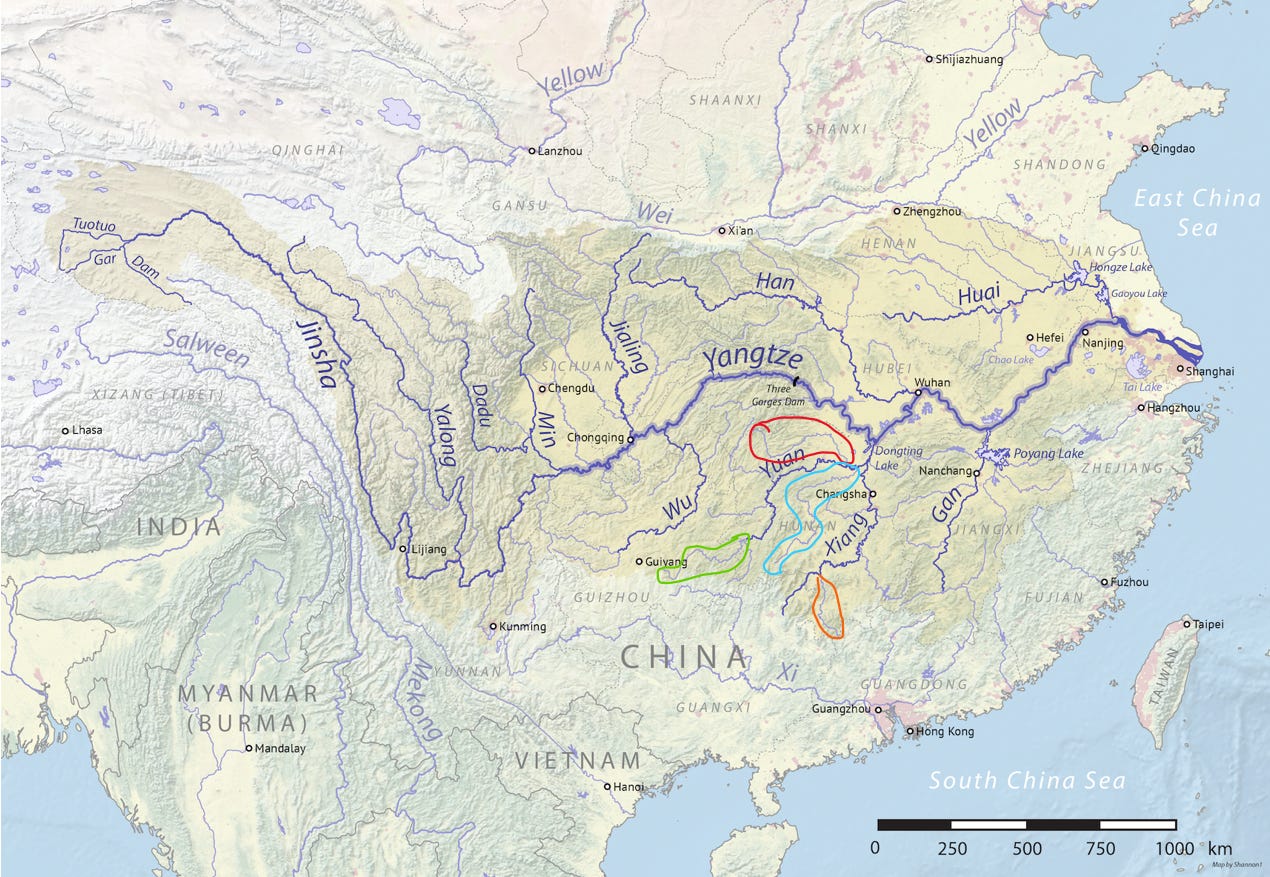

Almost all Hunan rivers smaller than these four still use 水 in their names. From looking at a list of Hunan rivers, it seems ~80% of all the rivers in Hunan have it. In the Yangtze River drainage basin map below, I’ve circled the Li River in red, which flows through northern Hunan before meeting the Yuan River. The Zi River is in light blue. I have also circled other examples of rivers using the 水 suffix, including the Xiao River 潇水 in orange as well as the Qing River 清水 in green.

Jiangxi is similar to Hunan, although a little less extensively 水-ified than Hunan is. While the major river in Jiangxi - the mighty Gan River 赣江 - uses a 江, quite a few smaller rivers in Jiangxi still use 水. It isn’t quite as prevalent in Jiangxi as it is in Hunan. I estimate maybe 50% of the rivers in Jiangxi use 水.

This includes the He River 禾水 (in red on the map below), the Zhang River 章水 (in green) and the Gong River 贡水 together with its upstream tributary the Xiang River 湘水16 (in light blue).

Outside of Hunan and Jiangxi, the only other instances of 水 I could find were some pretty small waterways in Hubei (Yun River 涢水) and Anhui (Hui River 徽水) and it wasn’t even really clear if those rivers still use those names today in regular vernacular, having been replaced with other names, or having already added an 河 on the end.

I searched extensively for a linguistic, cultural, historical, or geographic reason why these regions preserved their 水 river names, while most others did not, but failed to find a really convincing explanation other than they may have an connection via the ancient Kingdom of Chu (楚国). Perhaps one of my readers can offer a better clue.

Linguistic Fossils: 川 - The True Oddity

And that brings us to our second (and far rarer) living linguistic fossil for a way to say “river”: the character 川 (chuan1).

川 is an ancient character, a pictogram almost as old as 水 itself, emphasizing the geographic form and pathway of a river. The ancient 川 was used as a general term for rivers, similar to how 河流 is used in modern Chinese. Consider the illustrative line from the classic Zhuangzi - Autumn Floods: 秋水时至,百川灌河 (qiu shui shi zhi, bai chuan guan he; “during the autumn floods, a hundred rivers pour into the Yellow River”). This text even uses 河 in its ancient proper noun form to refer explicitly to the Yellow River, perfectly contrasting how 川 at the time was a generic term for rivers.

However, the meaning of 川 later shifted to encompass the flat land next to the river, picking up the meaning of “open plain” as in the idiom 一马平川 (yi ma ping chuan; “wide open country”). These days, 川 is used in place names, classical literature, and old idioms, but doesn’t have much use in modern vernacular language.

Chinese learners - even those who never learned much classical Chinese (like me) - would have learned about 川’s very archaic definition as “river” pretty early on in Chinese class. Actually, we likely learned about it in the context of an error, when learning about Sichuan Province and hearing an explanation that went something like: si = four and chuan = river, so Sichuan means “four rivers”. This explanation is mistaken - an example of “folk etymology” that a great number of Chinese people believe as well.

Sichuan’s name actually came from an old Song Dynasty regional term 川峡四路 (chuan xia si lu; “The Four Circuits of Chuanxia”) - a circuit being an administrative unit similar to a prefecture. Under the Yuan Dynasty - which succeeded the Song - this region with its four circuits was directly abbreviated to the “Four Chuan” Province (i.e., Sichuan). Meanwhile, the 川 definitional evolution from “river” to “plain” was already underway during the North and South Dynasties period, at least 500 years prior to establishment of the Song Dynasty. So, by the time of the Song Dynasty, the name Chuanxia 川峡 would have meant “plains and gorges”, not “rivers and gorges’ (referring to the topography of East and West Sichuan, respectively).

川’s definition as a plain is used still in modern place names all over the country today, thanks to the Song administrators’ great fondness for naming their administrative units after river plains (Yinchuan, capital of Ningxia, is another example).

But…here’s where it gets strange. 水 was the ancient term used as a generic suffix for river names in China. 川 was not - it was a general term for the category of waterways called “rivers”, and then later it meant “river plain”. Based on the various definitions of the character 川, it would never have been standard practice in China to have a river named the “something 川”.17

…so why are there a few rivers in modern China named the “something 川”?

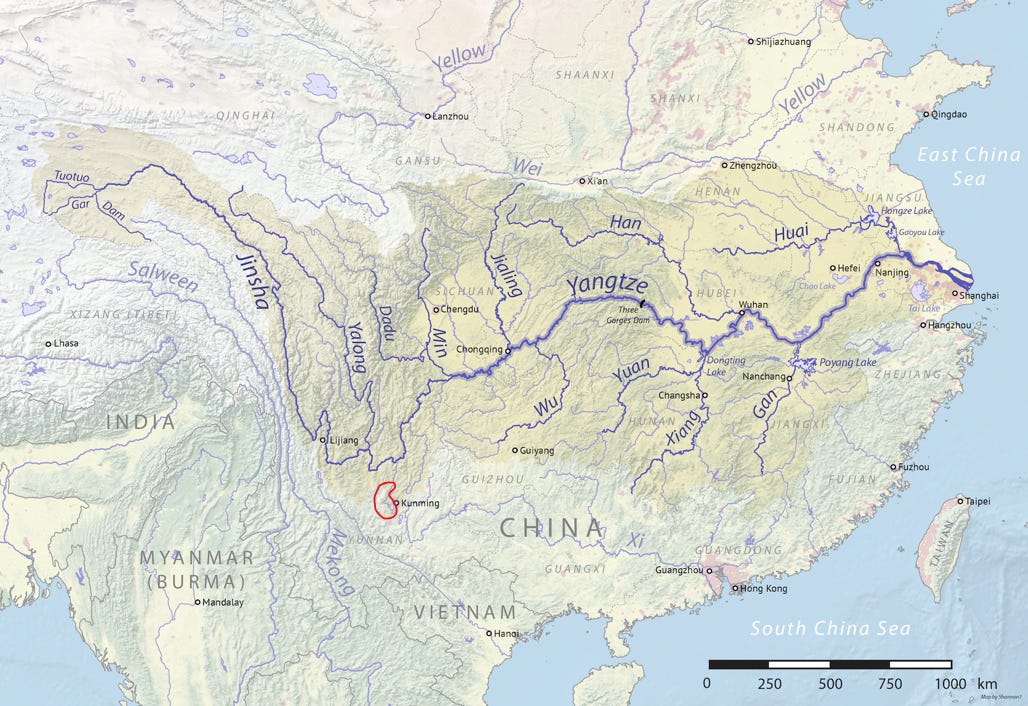

After an exhaustive search, I found three cases of rivers using 川 in their modern names in western China - two in Sichuan and one in Yunnan, two of them fairly large.

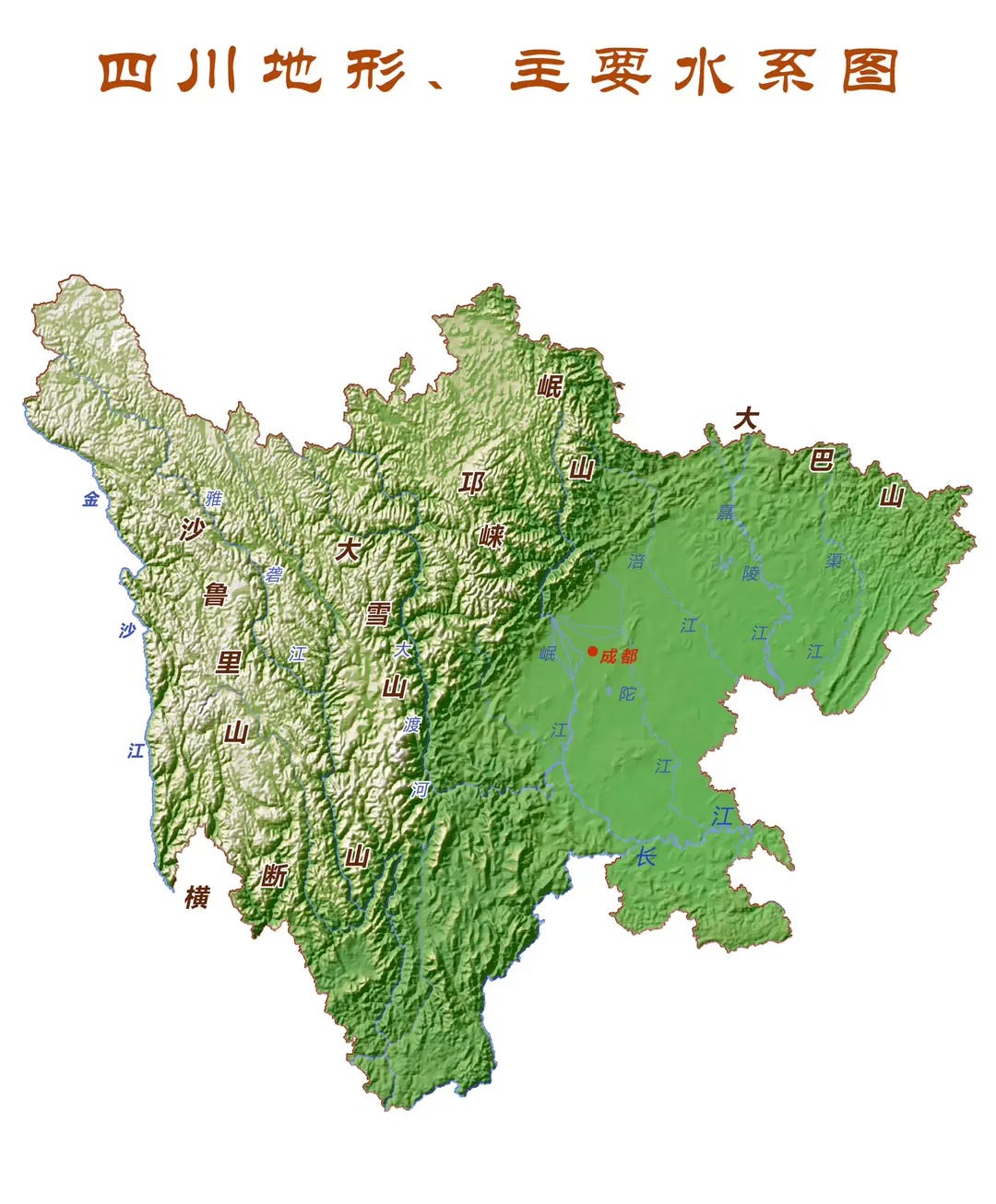

The 大金川 (Da Jin Chuan; “Dajin River”) in Sichuan flows through remote, mountainous regions of western Sichuan. After merging with the 小金川 (Xiao Jin Chuan; “Xiaojin River”), it becomes the Dadu River (大渡河), which further downstream in Leshan eventually merges the Min River (岷江), a major Yangtze tributary that dumps into the Yangtze at Yibin. Because the Dadu/Dajin combined length is longer than the Min’s own length, the Dajin River is thus considered the true upper trunk of the Min River.

In the map below, I have circled the Dajin River in red. The Xiaojin River is too minor to be visible on this map.

When reading about rivers using the 川 suffix online, I frequently found people on social media would tack a 河 onto the end - e.g. 大金川河 (Da Jin Chuan He; “Dajin River River”). This is not the official name of the river and is not the name that appears on maps or government documents, but it seems to be necessary for reading comprehension, given the rarity of this naming convention.

The other notable example of a river named 川 today is the Tanglang River (螳螂川) in Yunnan, the only outlet river from Kungmin’s 滇池 (Dian Chi; Dian Lake) which flows north of Kunming before turning into the Pudu River (普渡河) and then dumping into the Jinsha River (the Upper Yangtze). As far as I can tell, this is the only 川 in Yunnan.

But why are these rivers named 川, this ancient, anachronistic word that never actually was meant to be used as a generic suffix to mean “River”?

After a lot of research, one mostly-convincing explanation I found was the current names of the Dajin and Xiaojin Rivers probably originated via a process whereby the name of a well-known geographical area is subsequently transferred to its primary geologic or natural features…

This is an example of “toponymic transfer” and it was another new word for me.

The explanation goes like this: Initially, these rivers had names utilizing the 水 suffix. Meanwhile, the adjacent flat, habitable valley plains were designated as the 金川 (Jin Chuan; "Gold Plain"), a name reflecting the area's physical geography and its historical association with gold resources. This name Jinchuan was subsequently adopted as the official name for the administrative county (金川县; Jinchuan County). Over time, through constant association and common local usage, the word for "river" (水) was dropped when referring to the waterway itself. The name of the plain, 川 was thus re-applied to the river, a shift semantically supported by the character's ancient meaning of "river." Finally, the two main branches of this river system were distinguished by size, becoming formally known as the 大金川 (Da Jin Chuan; "Large Gold River") and 小金川 (Xiao Jin Chuan; "Small Gold River").18

Similarly, the 螳螂川 (Tanglang Chuan; “Mantis River”) clearly flows though a wide, flat river plain that could have started out as the actual reference for the usage of 川 in this region, before eventually transferring its name to the river. This explanation mostly resolves the mystery for me, although it’s still just a theory.

And it gives us our answer to the question asked in my title as well: What is the rarest way to say “river” in China? It’s 川, the toponymically confused linguistic fossil of a character that’s probably older that the written record itself in China.

Closing Thoughts

Thanks for coming on this winding journey (like a river, yuk yuk) with me to uncover the history of Chinese river naming conventions. If you've made it this far, following all the twists and turns from 水 to 江 and 河, then sincere kudos to you.

I must be transparent about how this came together. This essay would have been virtually impossible to research and assemble without the help of an LLM as a digital research assistant. Don’t get me wrong: I wrote it myself - every single word. I didn’t even use the LLM to “polish” or “refine” anything. But the truth is, while I’m fluent in modern Chinese, I hardly can read more than a few words of Classical Chinese, and before this week, a classic text like “The Commentary on the Water Classic” was definitely not on my radar.

Without Deepseek scanning literally millions of pages of classical texts to find every mention of a specific river suffix, the core section of this essay (the historical transition from one naming convention to another) would have been just a couple of speculative sentences. The AI found the examples and quotes that let me build a real, evidence-based narrative. Then, I double-checked every text myself to make sure there were no hallucinations…It was a fascinating process, like having an incredibly knowledgeable but also bumbling and dopey and easily-confused research assistant who constantly needs guidance to get back on topic.

Anyway, I'm glad I got to share the results with everyone. Thanks for reading. And if you liked - consider subscribing. It’s free and you can always unsubscribe later.

Footnotes

Li was commentating and adding to an earlier work - the《水经》(Shui Jing; “Water Classic”), written some 200 years earlier during the Three Kingdoms period - the original text of which has been lost and is only preserved within Li’s work. He expanded the older texts massively with his own extensive knowledge and annotations. It can be assumed that Li, whose official responsibilities directly included inspection of waterways, would have updated the names of any rivers that may have changed in those intervening 200 years, and that his hydronyms would have been fully up-to-date for the time.

For example, the《史记》Records of the Grand Historian, completed around 94 BCE by Sima Qian. In it, describing the Qin Emperor’s tour of inspection over his new empire, he records the emperor’s visit to modern Hangzhou’s Qiantang River 钱塘江 - famous for its powerful tidal bore - writing: “he reached Qiantang and came to the Zhe Jiang; the waves were fierce…”. (至钱塘,临浙江,水波恶). In this example, Qiantang is the name of the county and “Zhe Jiang” is the name of the river itself, sans the suffix word that would have meant “river”, omitted for brevity in classical Chinese. At the time, the river would have been called either the Zhejiang River 浙江水 or the variant Jianjiang River 渐江水, using the 水 suffix. The latter is how it was still recorded nearly 600 years later in the Commentary on the Water Classic. A further question may be: how did a river that wasn’t the Yangtze or related to the Yangtze come to have a 江 in its name at all? The odd presence of the 江 character can be observed in the Commentary on the Water Classic for several other river names in this region too. One theory is that such names actually have nothing to do with the Yangtze River, and instead were an attempt by Han Chinese settlers to approximate the sound of a word for the local river’s name in the ancient Baiyue language.

Modern day Yueyang City, Hunan

卷二十八·江南道四·洪州·豫章县 《元和郡县图志》

The Jinsha River was not properly identified as the true upper trunk until the fieldwork of Ming Dynasty geographer 徐霞客 Xu Xiake in 1638.

“四㑹者東有古津水湞江西有建水北有龍江四水俱臻因以為名” 《太平寰宇记》

“南方之人谓水皆曰江,北人谓水皆曰河,盖从其俗也” 《宋景文公笔记》

Although there IS a 黄江 “Yellow River” in Shanwei, Guangdong. And also a 黄江河 Huangjiang River in Dongguan (which literally translates as “Yellow River River”).

If you’re not in China, it’s much easier. Virtually all non-Chinese rivers are given a 河 for their name when translated to Chinese, like the Nile River 尼尔和, Amazon River 亚马逊河, or Mississippi River (密西西比河). The only exceptions for foreign rivers to use 江 are rivers on Chinese borders that also have Chinese names - like the Yalu River 鸭绿江 - or are part of China’s historical cultural and linguistic sphere, like North Korea’s Taedong River 大同江.

Incidentally, the name of Jilin Province also stems from a Manchu phrase (ula gilin) meaning “along the river”.

For instance, 黑龙江 Heilong River was known as the 黑水 until the Liao. The History of Liao - Chronicle of Emperor Daozong records the first instance of Heilong River being called the Heilong 江 in the 11th century. Meanwhile, the 松花江 Songhua River was known as the 速末水 until the Liao Dynasty, when its upstream estuary - today’s 嫩江 (Nen River) - was renamed the 纳水 and the downstream portion was designated the 鸭子河 - losing its 水 name. The Nen River got its first non-水 name in the Yuan dynasty. Both river sections got their current names in the Qing Dynasty (starting from 1644) based on transliterations of Manchu words.

Which becomes the Mekong River after it leaves China’s borders.

A reader pointed out the 北九水 of Shandong, which is firmly within 河 country, although it does not appear to be within the Yellow River drainage basin. Another mystery/oddity to puzzle over. But that’s the only one…

I’m willing to accept 汉水 is likely still relevant in historical, literary, or cultural discussions, but just can’t find much evidence of anyone using 汉水 in the common vernacular to refer to this river. Maybe local dialects still refer to it in that way. Other examples that were frequently cited but seemed to be in a similar situation were the Xiang River 湘江 and Yuan River 沅江, both major tributaries of the Yangtze in Hunan. While dialects spoken by locals may have preserved the ancient names using the 水 suffix, and someone looking to highlight the literary, cultural or historical aspect of these rivers might still call them 湘水 or 沅水, their names on modern maps definitely use 江 today.

Note that some sources call it the “Lishui River” in English - probably to differentiate from the more-famous Lijiang River of Guilin. Technically, both mean “Li River River”.

Yes, that’s right. Jiangxi has a river called 湘, which means “Hunan” and is also the name of the largest river in Hunan. There is no longer a 湘水 in Hunan itself, which now calls its major river the 湘江, but there IS a 湘水 in neighboring Jiangxi.

Japan would though. Contrasting its now very-limited usage in modern China, 川 evolved into the standard generic suffix for river names in modern Japanese, for instance, the Edo-gawa, or Edo River is 江戸川 .

The names 大金川 and 小金川 are deeply rooted in history, as they were also the names of two powerful Tibetan Chieftains in the region. The Qing Dynasty's famous Jinchuan Campaigns (1747-1749 and 1771-1776) were fought to subdue these chieftains, cementing the names in historical records.

<<I initially really only set out to write a small article about .... and accidentally got shunted into a week-long research mission to understand Chinese historical river naming convention>>

haha we all do that! China is full of lots of rabbit holes to go down!

thanks for this excellent article. Always wondered what the difference was between 江and 河 - know I know. Also in Laoshan (shandong) there is 北九水 - I always wondered why it was called 水 . sorry to add a northern holdout - any ideas why? I've done a quick search and come up with nada.

Thank you for being so upfront about your research methods. I've come to the conclusion that using AI for research is legitimate, its just faster google, but very different from using AI to write, which is based on the stolen work of millions of writers, across time and space.

A really fascinating article. So by this logic, the origin of the folk saying which lends it self must have originated in the north, in the Yellow River basin!!

Oh, also, Colin Thubron's book on the Heilongjiang, "The Amur River", is fascinating!

Thank you for this beautiful piece of work. A perfectionist you sure are. And please no worries about LLM doing your writing for you!! Your limpid prose with occasional quirky humor is already your personal trademark no one can imitate or duplicate, let alone improvable by a machine.

I don't remember if I read mention of how historically 江, as in 长江 , also named Yangtze, rises at the Tibetan Plateau and flows 6,374 km, including the Dam Qu River which is the longest source of the Yangtze, in a generally easterly direction to the East China Sea. It gets to be called 江 for that reason. There is a romantic mystique to Yangtze as well because for millennia, the river has been used for water, irrigation, sanitation, transportation, industry, boundary-marking, and war.

In terms of man-made canal, another term frequently used to indicate it is not a natural waterway is 运河, or 運河 in Traditional Chinese, where the first character denotes the purpose of the man-made "river": for transport.

In terms of the character 川, the character since its first appearance is the drawing of flowing water, whereas 山 is the drawing of mountains. Chinese is a fascinating language in that sense because the characters all began as drawings. Of course they also went through many rounds of "evolutions", but the nature of their being drawings in the beginning has not changed.