Off the Beaten Track: How is Life in China's "Most Median City"?

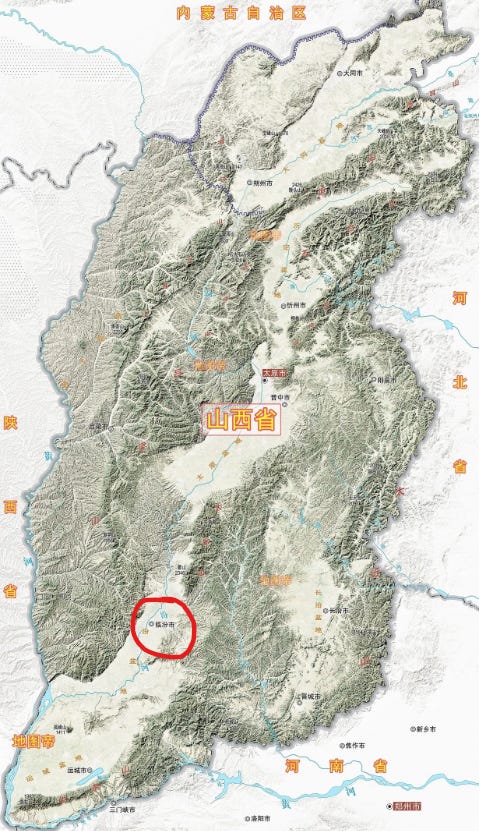

A deep dive on-the-ground exploration of Linfen City, Shanxi province

I just spent several days exploring the city of Linfen (临汾) in southern Shanxi. Linfen could be the most average city in China - at least that was my hypothesis before arriving. But what does that even mean? And why does it matter? In this episode of Off the Beaten Track, I went to Linfen to try to answer those questions.

The Most Average City in China?

Haven’t heard of Linfen? Don’t worry…you’re not alone. I’m a geography buff who’s been living and traveling in China for the past 14 years, and I hadn’t heard of it either - nor had virtually any of my Chinese friends with whom I shared my travel plans in advance. Straddling the Fen River, Linfen (literally: “close to the Fen River”) is a city virtually defined by its unremarkability.

In the annual Chinese city tier rankings released by Chinese financial magazine Yicai, 337 prefecture-level cities are ranked by their overall commercial competitiveness across a wide array of evaluation criteria. Naturally, booming metropolises like Beijing, Shenzhen, or Chengdu score highest, up in the 1st Tier, while mountainous backwaters in undeveloped regions like Tibet or Qinghai score lowest, down in the 5th Tier. The 4th Tier city #169 is the median - theoretically the most middle-of-the-road city in China. In 2025, that city is Linfen.

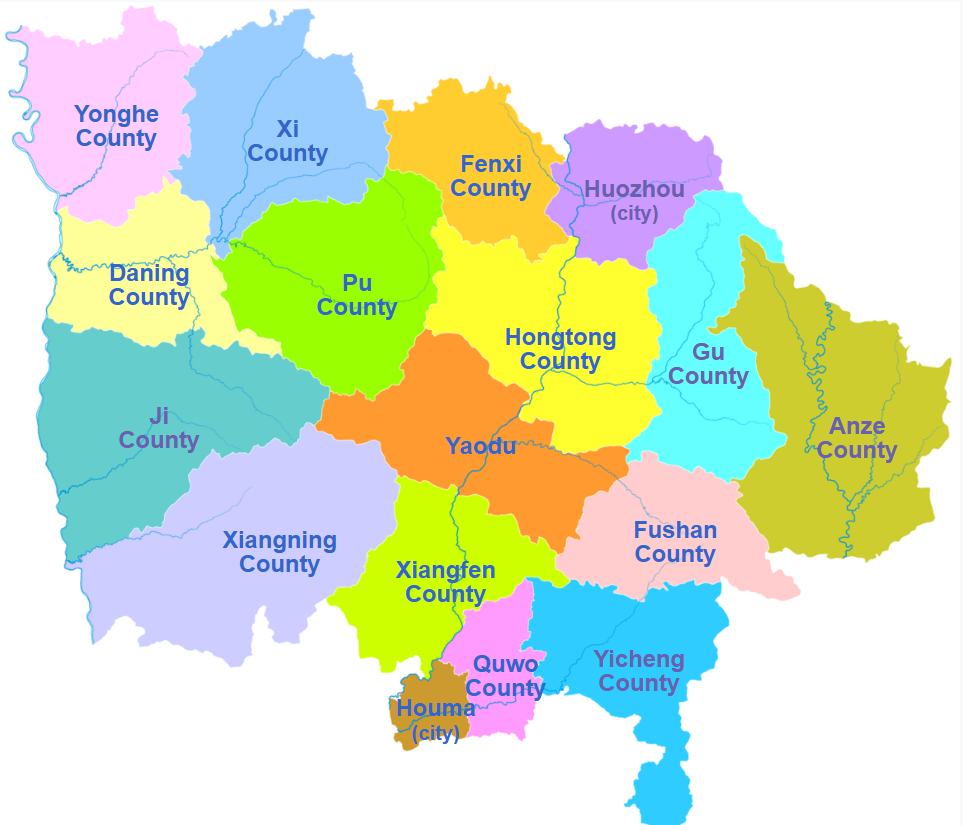

Linfen is an ancient city - and perhaps was even one of the first capitals of China (if you subscribe to the popular legend that the mythical Emperor Yao located his capital here in prehistoric times). In modern times, however, Linfen’s stature is a little more modest. With a downtown population of 1m and a total administrative population of 4m, Linfen is neither large nor small, neither rich nor poor. Linfen comprises a fairly large chunk of real estate. Like all Chinese prefecture-level cities, it encompasses both an urban downtown area (“Linfen proper”, which in this case is just Yaodu District) plus many distant satellite counties and cities.1 Thanks to its mountainous terrain, traveling from its northwest tip in Yonghe County to its southeast extremity in Yicheng County is a 300 kilometer drive requiring 3+ hours.

Arriving at the airport, I told my taxi driver I was an academic, coming to Linfen to study the development of China’s smaller inland cities. It’s a half-truth at best, but it certainly easier than explaining my odd interest in trying to understand China’s development via social ethnography. “I’m here because I think Linfen is an extremely typical small city in central China - not better or worse than any other cities, but just representative. Do you think this is a reasonable idea?” He chuckled. “Very reasonable. There are many Linfens in China.”

Downtown Linfen indeed has a very typical basic Chinese urban structure. There’s an older city quarter where small shops and rows of haphazardly parked scooters flank narrow, claustrophobic streets, but also an Economic Development Zone with broad sidewalks and broader streets tracing out a forest of glittery glass-paneled office towers. The park-filled greenways lining the Fen River are tidy and new, and the bridges light up with rainbow LEDs at night. There are creaky old department stores with brands you’ve never heard of, but also a new Wanda shopping center with a Starbucks, Huawei, and Li Ning. There are wet markets that stink of overripe fruit and fish guts, and clean modern grocery stores with imported French cheese and bubbling tanks of live Alaskan king crabs…

The streets heave with a frothing stew of e-bikes and gas-powered farm tricycles lugging burlap sacks of apples, but also BMWs and new electric mini-buses. There’s a (restored) Drum Tower, a (restored) section of ancient city wall, and a (restored) God of Wealth temple. You’ve never been to Linfen, but it doesn’t matter, because if you’ve visited a medium-small Chinese city in the last decade, then you kinda already have.

The Invisible Industrial City

“Hey, don’t take this the wrong way…” I told barista Zheng at the trendy coffee shop next to the God of Wealth Temple. “…but I think Shanxi might be the most invisible province in the country. And Linfen is an invisible city in an invisible province…”2

He laughed. “No, you’re right. Shanxi is invisible. No one in the whole country thinks of us at all until the winter comes, and then we get a bit of attention, because then everyone needs our coal. But besides that, we may as well not exist.”

Like many cities of central-north China, Linfen is rich in coal resources - coking coal specifically - which originally attracted the steel industry in droves. At one point in the late 2000s, Linfen boasted as many as 200 steel foundries within its city limits, along with hundreds of coal mines. These enterprises brought economic development - but also severe pollution to its water, soil, and (especially) air. Exacerbating the issue, Linfen lies in a geologic basin surrounded by mountains, which serve to trap the blanket of smog. By 2006, the city suffered from a near-permanent haze, and the World Bank named Linfen one of the most polluted places in the world.

Unfortunately, although the pollution has improved, this is mostly what it’s still famous for today - if you’ve heard of the city at all. “In those days, the sun didn’t really rise,” Zheng told me. “The sky would get light, and you could see the light source moving across the sky, but the haze was so bad you’d never actually see the sun.”

Embarassed by the negative attention on its choking pollution, the local government took action. Steel mills received stricter emissions standards, unregulated private mines were shut down, coal washing within the city limits was forbidden, and expansion of new industrial capacity was strictly controlled. In the following years, the air gradually improved, and today I can say it’s not bad…for China anyway. Not award-winning or anything, but certainly no longer ranking among the worst in the world either. But the cost of this improvement was the substantial damage to GDP and employment. The biggest nail in the coffin came a few years later, when local champion Linfen Iron and Steel (Lingang) shuttered most of its production amidst industry consolidation in 2015-16. Linfen’s economy was shattered. Over 2015-2018, GDP basically flatlined.

From Heilongjiang to Shanxi, this is the story of many cities in China’s “heavy industry rust belt.” Following the downsizing of the traditional heavy industries, Linfen has sought a new economic identity, pursuing “modern metals”, solar energy, natural gas extraction, petrochemical refining, and tourism. According to its statistics bureau, it appears to be working. Linfen’s annual GDP growth over the last 5 years has averaged 6.3% - more than healthy - but GDP per capita was still fairly low in 2024, just 62,994 CNY per person, or about 67% of the national average.3

That’s the 2025 Linfen economy on paper - but what does does the city actually look like on the ground?

High Costs, Low Wages

“I don’t think Linfen has a good future” my airport taxi driver told me as we headed into the city. “That’s why I only drive part time here, when I have free time. Actually I work full-time in another city now. After Lingang downsized, thousands of jobs left too and there’s little heavy industry left now. There are few good jobs now - only low-wage jobs like retail or delivery.”

I asked if Linfen has any specialties it can use to promote itself. He laughed bitterly in response.“Hah! Linfen’s speciality is low wages and a high cost of living. Even though the steel jobs left, our prices are still high, based on the old days - and they haven’t come back down.”

Complaints about the high cost of living were common to all the locals with whom I chatted during my visit. Online, I found real estate in downtown Yaodu District listed for 9-10k CNY per square meter, an unremarkable number for a large Chinese city, but notably steep versus other 4th-tier cities, where something like 4-7k would be more typical. In Linfen, I could only find those “normal” real estate prices among older, secondhand properties, or by setting my location to one of the suburban districts. “Everything in Linfen is too expensive…even our taxis!” the front desk attendant at my hotel complained. “The flag fare here is 6 CNY…in Xi’an it’s 7 CNY! Why is it just 1 CNY cheaper than Xi’an? We’re much smaller than Xi’an.”

So…is Linfen’s problem more that things cost too much…or that wages are too low? Driver Huang taking me back to the airport on my last day believed the latter. “Taxi rates are just way too low in Linfen.” Huang told me. “I drive 9 hours in a day to make just 300 CNY (about 42 USD). A fare in the city can earn only the flag fare of 6 CNY. A trip out to the airport is one of the only rides worth anything.”4 A Meituan delivery driver I bumped into while ordering at Luckin agreed. “We only get 3.5 CNY per order. I need to deliver over 50 orders a day just to make 200 CNY. It’s tiring. But that’s the only kind of job for people like me in Linfen, since there’s little manufacturing here.”

However, barista Zheng put more emphasis on Linfen’s high cost of living. “I currently make 5000 CNY per month. That’s not a lot by the standard of large cities, but it’s okay for a small city. Together with my wife, our income is almost 10,000 per month. But my daughter is five years old now, and the little one is just one year old. There are so many things to spend money on now…the house loan, my daughter’s art classes, school supplies. By the time I pay for everything, the money is all gone. How could I save anything?”

Getting Out While You Can

Actually, there’s nothing wrong with the quality of life in Linfen, barista Zheng continued to tell me. It’s comfortable enough for a small city, for someone who just wants to “pass the days”, (过过小日子) especially if you don’t have many expenses. Its biggest weakness is that it lacks excitement, and opportunities to do bigger things. Zheng regrets having children so young (he’s 30 now). “If I had waited a few more years, I could have saved up some cash, gotten a little more comfortable, and I’d have less stress now. I got married and started a family at an age that’s considered normal for here…for a small city like Linfen. My parents were already starting to get anxious. But I wish I had waited longer.”

Though he hopes to find a opportunity to leave Linfen someday, he knows his dissatisfaction isn’t shared by everyone. “Our parents’ generation doesn’t think about these things so much. They only compare to the conditions when they were younger, so of course they say it’s better now. They live in comfortable houses, eat good food. It was much harder when they were young, so they don’t have many demands for the future now. They just hope I can have a stable job and a comfortable life close to home. But I think my daughter has better chances in a bigger city. I’m not the kind of person who hopes his daughter grows up to be a phoenix.5 That’s the kind of pressure that the kids in the coastal cities have, not here. But I hope my kids can go to a larger city to see more of the world.”

The front desk attendent at the Atour hotel shared similar comments about Linfen. “The city is doing okay. Definitely it’s better now than when we were young. But its prospects are still limited. I was in Beijing before. I signed up for college, but I didn’t finish. I had to come back and work. I’m the oldest one, so I take responsibility for my younger brother and sister. They’re going to college, so I need to make money here, help out my parents with their education fees. It’s 30,000 CNY per year for tuition…they could never afford that by themselves. But I wish I could have finished college. To tell you the truth, I don’t want to spend my life in Linfen. It’s okay here, but…there’s no future…” She couldn’t hide the resignation and disappointment in her voice as she imagined what her life might have been like if she’d stayed away from Linfen and completed school.

“We used to have one good university here…Shanxi Normal University. But in 2021, it was moved away to Taiyuan. Now there is a new college, the Shanxi University of Electronic Science and Technology, but it’s just a second batch (二本) school.6 I went over there and looked at it, but it seemed not impressive. I even thought it was a scam school at first. I guess it’s real though. This year, we had parents arriving in the fall to stay at our hotel and said they were here to register their kids to start college. They were from everywhere…Hebei…Tianjin…Chengdu. I guess the only people that wouldn’t go there are people from Linfen. Because if you had the chance to go to college, why would you stay here? Why wouldn’t you take the chance to get out?”

No Advantages for Industry

In the earliest years of China’s economic reform, the first to develop were the coastal provinces like Zhejiang and Jiangsu, able to leverage their ready access to ports and personal connections to the overseas Chinese disapora to attract investment spending. The inland provinces provided raw materials and labor to drive this boom. Only later in the 2000s and 2010s did the first ring of inland provinces begin to see a similar surge in manufacturing investment, as coastal producers moved inland in search of cheaper land and labor, setting up shop in nearby provinces like Henan, Anhui, and Hubei. But this wave of factory relocation has only occasionally swept so far inland as Shanxi, and when it does, it certainly lands in Taiyuan, the capital.

“Linfen’s biggest problem is our poor transportation development” barista Zheng told me. “We don’t have very big mountains, but they’re still mountains, and they block transportation. Compared to the coasts, or a province with good inland rivers, why should someone come here to open a factory? We can’t easily connect to the coasts, or the big cities.7 All we have is the capital, but Taiyuan is just a Tier 2 city, not so strong itself. Our only advantage is our coal. But now that we can’t use it for heavy industry, and we never had a chance to develop light industry either, so what are we supposed to do? There’s not much opportunity in Linfen. This is why we have so much brain drain to big cities.”8

What about the Fen River? I wondered. Can you transport goods to the coasts via the city’s namesake, this famous tributary of the Yellow River? “Hah, it’s almost dry now” Zheng chuckled. “The droughts in northern China are so severe. When I was young, it was navigable by boats, but now? Forget it! This year we had very weird weather in Shanxi and it rained for two months straight in the summer, so it was possible to take a boat on it, but it’s not normally like that. Our rivers are not like those in southern China. You can’t use them to transport goods.”

If manufacturing isn’t an option, then what about services? The local government is putting a lot of effort into promoting tourism. A lot of money has been sunk into improving local infrastructure, and clearly the hotel options are improving too (after all, there was a new Atour hotel for me to stay in). But Huang Shifu, my Didi driver back to the airport, was not so sanguine about the tourism prospects. “The city leaders plan to promote tourism…hah. I don’t believe in that. Sure, there’s the Hukou Waterfall, but that’s too far away from the city. And Xiaoxitian Temple became popular over the last year, because of the Black Myth: Wukong game, but that’s also far away. What does that kind of tourism have to do with Linfen city? That will only benefit those far-away counties, not Linfen.”9

He clearly believed that tourism in Linfen’s administrative hinterlands would have little impact on his life in Yaodu District. I understand his pessimism, though I am more inclined to take a macro view of the broader salutatory effects of tourism on the city’s economy.

“Our infrastructure is much nicer now, that’s true” he allowed, after I asked him about the city proper. “In the last two years, we’ve had a new leader in Linfen, and he wants to make the city more beautiful for tourism, so they are spending a lot of money in this way. Like those leaves” - he pointed to the bright yellow ginkgo leaves on the wet sidewalk - “those will be swept up before the end of the day. The improvement of the streets, the city wall, the renovation of the old God of Wealth Temple, this was all in the last few years. People always say Linfen’s streets are very clean now - even cleaner than Xi’an’s, and I think it’s true. But that won’t matter if there’s no tourists here.”

Was Linfen the Hypothesized Median City of my Dreams?

What did I learn in the end from my trip to Linfen? Well, I’ve been obsessed with this idea for a few years now - that understanding the mid-tier cities of China is key to getting an accurate read on modern Chinese politics, economics and society. After all, China’s Big 4 cities (Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Shenzhen) have a total population of just 84 million. After this, the total population of the next 15 cities (the “New 1st Tiers” like Hangzhou, Chengdu etc.) is roughly 200 million. Another 20% of the population lives in 2nd-tier cities, and then a full 60% of the population (840m+) lives in a 3rd, 4th, or 5th-tier city.

While I’ve concluded 4th Tier Linfen isn’t really a suitable proxy for median China, I think it’s a great representative of the “semi post-industrial north/central city trying to reinvent itself” archetype. In that regard, Linfen likely is an excellent stand-in for many small cities in Shanxi, Shaanxi, Hebei, Liaoning, etc. The recent boom in infrastructure spending, the effort to transition to new industries after severing ties of dependency with a polluting heavy industrial past, the improved air, the slower pace of life, these are all typical narratives that could belong to many parts of China.

But…it has some features making it less than ideal as national representative. The high cost of real estate is bizarre for a city of its size. Wage levels and goods prices seemed normal for a small city, but past years of uneven growth mean Linfen's GDP per capita still undershoots the national average. Most cities offer their highest living standards and wages in the urban center, but in Linfen, I found residents in the urban center to be most dissatisfied with Linfen’s prospects. Meanwhile, citizens in rural Ji County (which I’ll cover in a different post) were far more optimistic. Reviewing the regionality of the drivers of growth for the last few years helps to explain why.10

Can Yicai’s Rankings REALLY Lead Us to the Median City?

I came to Linfen because it was the median-ranked city in Yicai’s city tier rankings in 2024. But in 2023, Linfen was ranked well below the median - 23 spots lower actually, at #192. Yicai’s methodology puts a lot of emphasis on the city’s exposure to “new industry” segments like clean energy, and the city’s recent efforts to develop those sectors probably contributed heavily to Linfen’s rising rank this year. Everyone I talked to seemed to share the vibe that the city is doing okay but not great, with clear eyes on their limitations to growth versus more well-endowed regions of the country. It’s possible the transition to a stronger economic structure is already sufficently advanced to be captured by Yicai’s bean counters, but not mature enough yet to be broadly felt in all quarters on the ground. Maybe.

In 2022, Linfen’s rank was #146, so we’ve also got to consider there’s apparently quite a lot of methodological volatility going on here (although at least Linfen has always consistently been in the 4th Tier). Yicai’s ranking system has always been more focused on identifying up-and-coming top cities, and less-focused on implications for lower-tier cities.11

I thought it was notable that although Linfen has an airport, a high-speed rail station, and is served by at least three national expressways, the locals still consider the city to have poor transportation, limiting their options for growth. I’m not sure what else can be done in that regard. Frankly, I think they have pretty good hard transportation infrastructure now, but at this point are hemmed in by geographic realities. There’s little incentive for a manufacturer to site their production so far inland as long as closer options exist.

For Linfen and cities like it to survive the coming decades, a broad and proactive economic re-orientation is truly the only way. If the city can succesfully realign towards its new primary industries - ones more future-proofed against China’s energy transition - and complement it with tourism, it may be able to stem the brain drain and hold onto its people. While the taxi driver was pessimistic about the prospects for tourism, I think he underrates the economic draw of a 5A-rated scenic site (which Hukou Waterfall is). In any event, Linfen probably has a better shot at succeeding in this endeavor than other cities up in the northeastern provinces. But only time will tell.

The End…for Now

“Thanks for the talk. I’m heading to the airport now” I told barista Zheng, who had been such a champion, chatting with me all afternoon (the coffee shop was empty except for me, and he was bored).

“Oh…you’ve leaving! I hoped you were still staying another day in Linfen. I was going to invite you to dinner tonight. I would like to treat you to drink some of our local fenjiu 汾酒.”

“Unfortunately not this time…but maybe someday. If I come back to Linfen, I’ll definitely accept that offer. But you can also come visit me in Shanghai - I’d be happy to receive you.”

“Okay, let’s do that then. Let me add your WeChat. I hope to take my daughter to Disney in Shanghai someday.”

“Okay, it’s a deal. See you next time in Shanghai!”

-END

Footnotes

This seemingly-mundane detail is actually somewhat remarkable, because this degree of county-level administrative fragmentation (17) is rare. Linfen has more counties than anywhere else in Shanxi. There are only 3 other cities in the country that employ as many county-level divisions, and only 9 other cities that have more. Most have 5-10.

The phrase I used for “invisible” in Chinese is 没有存在感 - which is a bit tricky to render properly in English, but literally translates as “lacking the feeling of existence”.

Of course, it’s difficult to get a proper assessment of this figure in small cities like Linfen, where a large part of the registered population may actually live and work elsewhere, which makes visiting in person to get a feel for the city even more important.

My 25-minute airport ride racked up a healthy fare of 51 CNY, but with only 13 flights daily to Linfen’s small airport, there can’t be that much demand for rides to the airport.

望女成凤 - an idiom meaning “to have great aspirations for your daughter” (lit. “hope your daughter becomes a phoenix”). The corresponding version for boys is 望子成龙 (lit. “hope your son becomes a dragon”).

First-batch schools are the target schools for college entrance exam-takers; second-batch schools are seen by many as the “leftovers”.

Indeed, it was actually a bit of a pain to get there. I had been surprised to find almost all train options from Beijing or Shanghai required an inconvenient connection via Taiyuan or Xi’an, which is why I decided to fly in the end.

For Linfen, “big cities” doesn’t usually mean places like Beijing or Shenzhen. Instead, it means Taiyuan - the provincial capital 250km to the north - or Xi’an, the capital of Shaanxi Province, 380km to the southwest.

Hukou Waterfall is in Ji County 吉县 and Xiaoxitian is in Xi County 隰县, technically administered by Linfen but both 100+km from the city center.

For instance, Anze County in far eastern Linfen hosts a new petrochemical industry park and now boasts a GDP/capita that is much higher than the national average, but how much is this filtering back to Yaodu District?

Consider: in 2022, the median city was Zhoushan, in Zhejiang, which I think is a bizarre methodology artifact. Zhoushan is MUCH too wealthy to be considered median for the country, but I suspect its comprehensive score was dragged down by low transportation accessibility scores (Zhoushan is an island with no rail).

That was excellent, thank you! I don't know about "median" but you sure described the typical Chinese city! 😂😂😂 Tourism is their lifeline, a strategy shared by many recently. I remember writing such about Jingdezhen two years ago. Tons of potential there, lots of money going in, but when everyone is doing it? Another industry everyone is piling into meaning lower profits or losses for everyone.

The name Linfen rang a bell but after the intro I thought I am just mixing up the many similar Chinese names. But I could not let go, turns out I have indeed heard of it in the context of this absolutely astonishing photo series of Coal Cities from Ian Teh https://www.ianteh.com/dark-clouds/v2hko9n19dphek0h3w5cx49at4h6tl. Probably my favourite photo project I found out about this year. Wish I could still find a book of it.