Ordos City - The World's Most Famous "Ghost City" (That Isn't)

As soon as I knew I was going to be visiting Ordos City, Inner Mongolia in July 2025, I knew I was going to have to write an essay about “ghost cities” and whether Ordos is one (or not). This is that essay. Enjoy.

Concerning Ghost Cities

You’ve heard of Chinese “ghost cities” right? As the conventional China-observing wisdom goes, Chinese municipalities are prone to indulging in wasteful overspending, constructing vast cities where no one lives, complete with houses, malls, plazas and other public infrastructure that will never be used. Perhaps these projects are framed as ill-conceived white rhino boondoggles, the products of superficially well-intentioned ideas ultimately brought down by poor execution. Alternatively, these projects may be portrayed as cynical vanity projects intended only to jazz up GDP figures and advance the career interests of some local officials.

In such narratives, what eventually happens to the unused infrastructure is anyone’s guess - it likely just sits there decaying like the gold rush boomtowns of the American West, awaiting the visits of wide-eyed social media influencers. But who cares anyway? What happens later isn’t important; what’s important is that investments are wasteful and short-sighted, the quality of construction shoddy, and the GDP figures fabricated! The only real debate is whether it’s more appropriate to attribute this wasteful spending to regular, garden-variety incompetence…or intentional dishonesty!

It’s such a neat, tidy story. A compelling, easy-to-understand “wow, you’ll never believe this thing in China!” that invites the reader to exclusive membership in a secret club of People Who Know Things - and who doesn’t like to feel part of an exclusive club of knowledge-havers?

Unfortunately for this particularly smug club of knowledge-havers, there’s a famous and particularly apt quote that deals with this scenario.

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble.

It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

- Mark Twain

Mark Twain surely wasn’t talking about China specifically, but the applicability is outstanding nonetheless: The broader ghost city narrative is nonsense.

Those Chinese cities “built for no one” don’t stay empty; over time they get filled up with people who come to partake of the infrastructure that was built in advance for them. The oldest and perhaps famous example is surely Shanghai’s Pudong New District, the original “ghost city” east of the Huangpu River, the empty buildings of which Milton Friedman famously sneered at in 1988 upon visiting, declaring it “a statist monument for a dead pharaoh on the level of the pyramids”.

Over the 1990s and 2000s, the formerly-rural Pudong absorbed new residents at a steady clip as Shanghai itself swelled. Today, it is Shanghai’s most populated district, boasting a population of 5m people, exceeding the population of roughly 75 countries worldwide. Over 300k people work in the financial district of Lujiazui alone.

Comparable outcomes have been observed in Tianjin’s Yujiapu District and Zhengzhou’s Zhengdong New Area, to name a few other prominent examples of development zones previously dubbed ghost cities. On public infrastructure, China passes the puck to where the skater is going, not where he is right now. They simultaneously also tell where the skater where the puck is going, so he knows where to skate. It shouldn’t be surprising that this approach scores quite a few goals. In fact, the only surprising thing at this point should be the determination of foreign observers, especially the press, to forget how many times China has done this already.

Now of course, I would be remiss to not take a moment here to contrast China’s broadly effective and successful municipal planning initiatives with the hordes of failed real estate ventures, of which there are many, especially from private developers. When it comes to residential real estate, there are too many to list, from villa districts build in undesirable locations that never found buyers, to vast forests of half-finished concrete shells abandoned by an indebted developer (e.g. Evergrande and its peers), to residential districts where every unit is owned by someone, but no one lives there because the unit was only intended as an speculative investment asset.

These should be not conflated with the intentional urban planning initiatives like Yujiapu or Zhengdong, where entire cities - complete with malls, public transit, plazas, and public facilities - were constructed in advance of the people moving in. These are something else entirely, and although they are interesting and worth their own deep-dives, they are not the “ghost cities” of which I write here.

Concerning Ordos

Now we come back to Ordos, a frontier-esque Inner Mongolian city on the edge of the Gobi desert, boasting the highest GDP per capita in the country, known for its larger-than-life (and infamously uncouth) coal bosses, heavy industry, massive abundance in clean energy…and its very own ghost city - at least as the story goes.

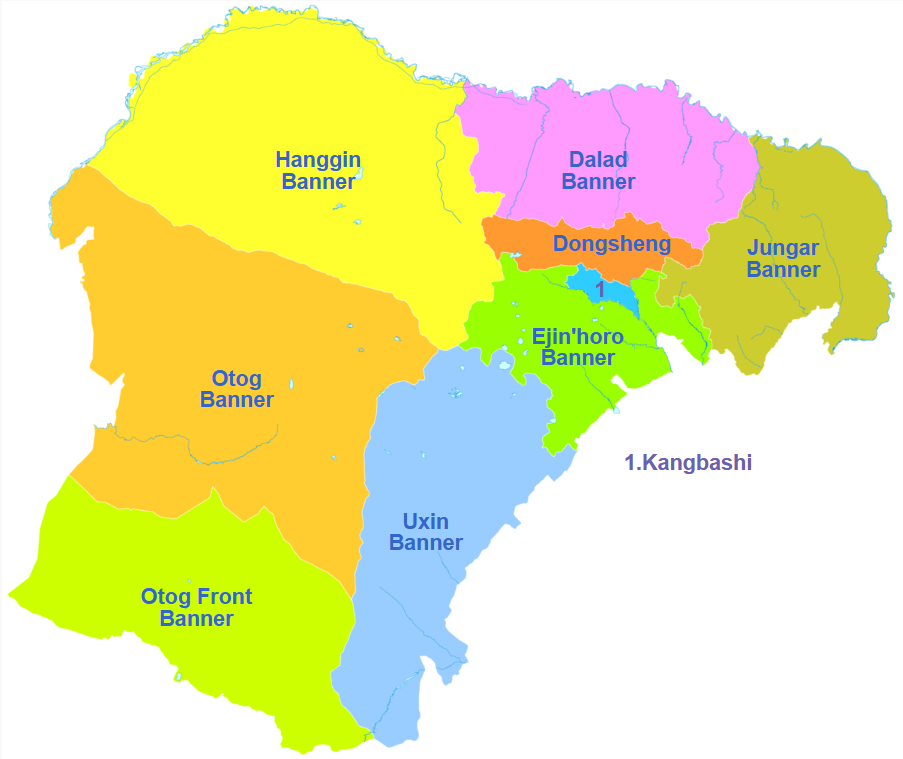

The image above is the administrative structure of Ordos City, with its old city center (and still most densely-populated zone) in Dongsheng District. The total administrative population of Ordos is 2.1 million, but the core metro area has only around 700k. Those rural counties around the periphery like Dalad Banner (where I visited a giant solar farm in the desert) are very large and sparsely populated. Most of the population density is in Dongsheng and Ejin’horo.

Today, the region we need to focus on is Kangbashi (康巴什) District, sandwiched between Dongsheng District and Ejin’horo Banner. In past decades, this area was a barren desert region, with few settlements and little development. In the late 90s, it was designated an urban expansion development region for the rapidly-growing Ordos City called Qingchunshan Development Zone 青春山开发区. Then, in the early 2000s, bolstered by the huge influx of local wealth courtesy of the booming coal sector, Ordos city officials decided to transform Qingchunshan Development Zone into a new planned urban community as the proud new capital region of the wealthy young city. This region would be called Kangbashi New Town.

From 2004, construction began and Kangbashi New Town slowly took form, with planning on a grandiose scale: wide avenues, large apartment complexes, huge municipal features, the works. Over a 12-year formal construction period, the desert was slowly transformed into a moden urban hub, plazas and roads and municipal amenities sprayed over the the formerly barren earth. After the formal construction period ended in 2016, Kangbashi New Town was re-designated as Kangbashi District.

The human scale of Kangbashi was intially envisioned and designed to be able to accomodate 1 million people. This seems very ambitious, considering that was basically 50% of the whole population of Ordos in 2004. But coal prices were high and the industry was booming at the time, so massive growth was anticipated. Later in the decade, following the decline of coal prices, ambitions were tempered somewhat and the scale of the planned district was scaled back to 300k people by 2020.

In its earlier years, when the district was still under construction, there was really no compelling reason to live there, and residency rates were low, even though the residential units were were mostly finished. Ordos City moved its municipal government to Kangbashi in 2006, but that didn't necessarily tempt people to move in. Even the public servants would commute to work in Kangbashi from their homes in Dongsheng or Ejin’horo.

Our local driver told me that in those days, property in Kangbashi was dirt cheap - as low as 2000-3000 CNY/sqm, and it sold well, with plenty of willing buyers in wealthy Ordos, but no one wanted to actually move in yet. The properties showed enough potential to justify investing as a store of wealth, but few were lining up to move their families into an unfinished city. By 2009, the district’s resident population had only reached around 30k people. The grandiose scale of construction with few pedestrians only exacerbated the sensation of emptiness.

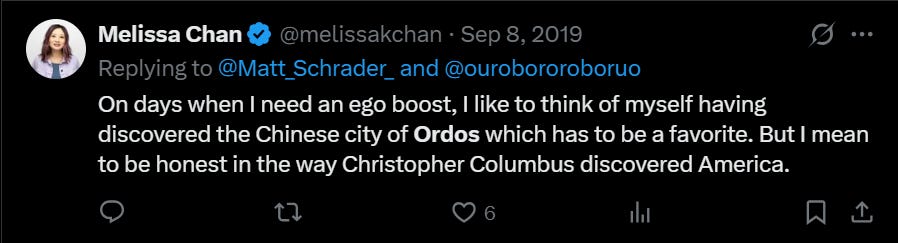

2009 was the year Kangbashi got unlucky. Barely halfway through its construction and development phase, sporting mostly-empty buildings at just 10% capacity, it was "discovered" by foreign media, specifically an American reporter with a distinctly China-unfriendly slant to her work named Melissa Chan, at the time writing for Al Jazeera.

"Welcome to the city of Ordos, a city of the future,” Chan’s 2009 video report starts. “Brand new and built in just 5 years, and meant for 1 million residents. But no one’s moved in, the city stands empty."

Sadly, Chan’s report for Al Jazeera was rife with journalistic carelessness. In that 2009 story, she misreported several important facts in the first line alone, failing to correctly identify both the under-construction district and its planned size. Remember, at this time Ordos was already a full-fledged city with 2m people. Kangbashi New Town (later District) was the under-construction planned urban community meant for a (revised-down) 300k people with a target date of 2020 - both significant flubbed details. On her follow-up report from Ordos in 2011, Chan continued to misreport both of these items.

Indeed, it really is a shame it was Chan who stumbled across the under-developed Kangbashi in 2009. After observers had previously misjudged places like Pudong New District, here was a fresh opportunity to closely examine China’s “planned city” urban development model in real time, evaluating what adjustments had been made or lessons learned vs prior efforts like Pudong. But this was never a task someone so lacking in nuance and professionalism would be able to perform with sophistication. Instead, her reporting dissolves into simplistic smugness and glee for having discovering “proof” of Chinese manipulation of GDP growth. Although the original Al Jazeera piece didn't specifically saddle Ordos with the "ghost city" moniker, (that came in 2010 with a Time Magazine photo essay) it sure got the ball rolling. Over the following years, many more journalists, international and domestic alike, would travel to Ordos - the city build for no one - to gawk and sneer.

Of course, the problem is: it didn’t stay empty.

Kangbashi DID fill up! Not overnight, not suddenly, but slowly, over years. In 2024, Ordos’s Kangbashi District had an official population of about 130,000 people, and still rising. Is 130k the same as 300k? Definitely no. They’re still considerably trailing their targets, but it’s a process, and the process is clearly still moving forward. Very likely it'll be clean energy and industry that propels Ordos forward now, not coal, and there's no reason to be bearish on that sector’s long-term outlook…

That’s what I saw on my visit to Kangbashi in July 2025. The streets indeed were hardly thronging with pedestrians, and the massive 4-lane separated highways still feel too large for purpose right now, but the place clearly has more than a few people living there. The housing which used to be empty is now full, as are the office buildings. Owing to the distinct lack of walkability of the urban design, you still don’t see many people on the streets: just long streams of vehicles, ferrying humans from home to office. It’s more reminiscent of American strip-mall suburbia than an organic Chinese city. But it’s definitely inhabited by more than ghosts.

But even today in 2025, the ghost city reputation persists, and it’s still hard to avoid encountering misinformation when looking for up-to-date information about the city. if you Google “Ordos”, the #2 result after Wikipedia is a BBC article from 2012 (13 years ago!) describing Ordos as “the biggest ghost town in China”.

If this article I’m writing is popular enough, perhaps it can someday land in the top 10 of the Google search results, maybe even displacing the BBC. We can only hope.

The Consequences

Now, a reasonable observer might ask…why should we care? What is the value of relitigating sloppy reporting from 16 years ago? Isn’t that ancient history at this point?

Well…because that sloppy reporting ended up having major consequences. This misidentification of the ghost city as Ordos itself and the missing historical context was repeated in much of the subsequent coverage, picked up by hundreds of news organizations, even including Chinese domestic media! In China, it’s one of the first things even Chinese people think about when Ordos is mentioned: an empty husk Potemkin Village exemplifying wasteful spending in pursuit of GDP manipulation.

Naturally, Ordos locals are aware of and resent their ghostly reputation. Nearly every local I chatted with referenced at some point - often unprompted - the unfairness of the “ghost city” label, attached like an unwelcome wart to the city they love and call home. The Ordos of 2025 is not the Ordos of 2011, and they want you to know it.

“Honestly, Kangbashi is a miracle” our local guide Yang told me on my visit. “When I was young, I used to take a bus through there from Dalad Banner to Ejin’Horo. It was just a bumpy road through the desert. When the bus started bouncing over the potholes, that’s how you knew you were in Kangbashi. Now it’s beautiful.”

“Honestly, Kangbashi is a miracle”

Our van driver told us property prices and enthusiasm for living in Kangbashi really started to take off after the most prestigious middle school in the city relocated there in 2016. Before long, Kangbashi boasted the most expensive property in the city, with listings there even topping 10,000 CNY/sqm - 3x higher than just a few years prior - before the current property market downturn.

“It’s true” our loal coal trader contact Mr. Qi told me when I asked him about the significance of moving the middle school. “You know Chinese people…they will do anything for children’s education. Ordos Number 1 Middle School is one of the strongest middle schools in Inner Mongolia. Last year, it sent 33 graduates to study at Tsinghua and Peking University”.

[I checked on this number later, and was impressed by how many graduates this one school sends to China’s top colleges. Most equivalent schools in other cities would hope for 1-2 per year. It’s quite the outlier for a small city, but perhaps there’s an interesting point about Ordos’ high GDP per capita here.]

I’m hardly the only person to have visited Ordos since the sensationalist reporting from 2009 and found reality to be a little different. Even as early as 2016, 9 years ago, it was apparent Kangbashi was starting to fill up. That was the year travel writer Wade Shepard visited the city for a piece in Forbes. Even at that time, he was able to firmly reject the ghost city narrative, writing:

"a city built for nobody out in the middle of a desert... a fascinating, chilling story, but simply not true."

2016 was Shepherd’s second trip to Kangbashi, following a first visit in 2014 he detailed on his blog Vagabond Journey, where he first noted how Kangbashi was starting to fill up with people. I enjoy his writing, certainly in part because it resembles so closely the kind of writing I myself hope to do myself in this newsletter - broader observations backed by boots-on-the-ground exploration. He would later publish a book about China’s urban development model called “Ghost Cities of China” based on his time exploring these places.

Shepherd’s sadly-underlooked 2016 Forbes article corrected the worst errors from the 2009 Al Jazeera hit piece, including properly identifying the area as Kangbashi (not Ordos) and pointing out that Ordos itself has its own population of nearly 2m people. Shepherd, whom, from his social media writing is unlikely to ever be described as particularly biased in favor of China, ended up concluding the city should be celebrated as a success for its planned approach, while highlighting that the district is still extremely unwalkable, does not foster a sense of community, is overlarge for its purpose and forces everyone to drive in cars to get anywhere. Having just visited, I have to agree with all of the above.

Meanwhile, Chan has never acknowledged how badly she messed the story up…not just the specfic details on Ordos but for missing the opportunity to more thoughtfully examine China’s entire “build it and they will come” approach to urban infrastructure. I normally wouldn’t care much about poor reporting on China, since it usually has so little true effect beyond slightly sweetening the sour grapes of those who need an excuse to disparage what they can’t have. But the Ordos case has had uniquely deep and broad reverberations - both domestically and abroad. Chan’s reporting may have initially just been about sweetening sour grapes - but in the end those grapes turned to vinegar and that vinegar poisoned the narrative well around Chinese urban and infrastructure development strategy, even to this day. As recently as 2019, she was still bragging on Twitter about her work on Ordos, so it seems unlikely any acknowledgement or atonement is forthcoming.

Last Thoughts

Well, if there’s one thing from which to draw comfort, it’s that despite the mockery, China has continued with “build it and they will come” development strategies, even through the ongoing property crisis. I saw it firsthand when I visited western Hunan’s Jishou City (the capital of the Xiangxi Autonomous Prefecture) in 2022 and found Jishou’s new city district to be half-constructed and notably…empty. Fast-forward three years, and I am now spotting travel posts on Twitter showing the same ghostly and unfinished areas I had walked though in 2022, filled with people.

Even now, China’s urbanization rate is estimated at just 67%, and if you’re familiar with some of my past writing, you know I believe much of this so-called urbanization is of relatively low quality, with huge room still for expansion of high-quality urban development. This is to say, there’s still lots of latent demand for people to move into these urban centers, and it’s perfectly sensible for municipal planners to design these envisioned urban spaces in advance, ensuring they can focus on creating productive, livable, and environmentally resilient cities that are designed for people.

They can ease back on the scale and consider things like walkability more - yes - but I don’t think they should rein in the concept of planned urban spaces at all. But yes, that means there will be periods of time when these spaces don’t have any people in them. They might look a little silly. A little wasteful. A little empty.

That’s what happens when you build public infrastructure in anticipation of demand, rather than belatedly, in response to it…supply-driven growth. You might even call it evidence of China’s “abundance” mindset, if you’re feeling spicy and you feel like flirting with a hornet’s nest of Popular Discourse. Just please…don’t call it a ghost city.

Never ceases to amaze me the arrogance some people have when they are "reporting" about China. More than happy to make completely incorrect statements about something and then gloat about it a decade later. Anyone who has lived in China has watched new cities or areas being built, empty for a while then filling up before you know it. Wade Shephards' book did a lot to dispel that myth. Thanks for this post.

For a snapshot of the city in 2015, check out the photos in this piece: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/china-ordos-ghost-city-life_n_7204016

Yes, shameless self-promotion but the it's really about the pics by Matjaž Tančič.