A Photo/Video Essay: Driving National Road G214 North to Deqin County in Tibetan Yunnan

My journey through some of northern Yunnan’s most remote regions continues. Today, we’re heading north on the G214 National Highway from Shangri-la to Deqin County.

This is China’s National Highway G214 (Guodao 214). It’s the main highway leaving Shangri-la to destinations further north - a necessary route for further exploration of Tibetan Yunnan. It winds its way north through the valley gorge of the Jinsha River (金沙江), perched precariously on the cliff’s edge, with a sheer drop into the river on the left and stern mountains arising on the right shoulder.

I’m taking the G214 because Shangri-la was already the last destination in northern Yunnan that can be accessed by the ever-growing high-speed expressway network. Now it’s time for the Guodao network - a distant second-best choice speed-wise when expressways are available, but often much better for sightseeing. There are nearly 400,000 kilometers of Guodao (National Highways) in China, always identifiable by their characteristic signposts featuring white text on red backgrounds.

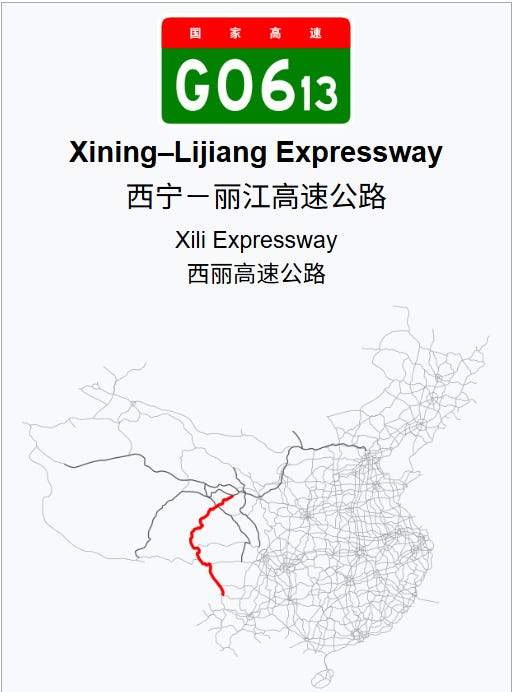

By contrast, high-speed toll expressways use white letters on green backgrounds with a red header. As of 2025, there are already nearly 200,000 km of expressways nationwide. I previously took the still under-constrution G0613 from Lijiang to Shangri-la. It will eventually connect north up to Xining, the capital of Qinghai Province, but for now it terminates in Shangri-la.

The Guodao are some of the oldest modern roads in China. Many of them originated 60+ years ago and were the first paved roads serving the regions to which they connect. Because of their age, they rarely use tunnels or bridge flyovers. If there’s a mountain in the way, they’ll just slowly zig-zag their way up one side of that mountain, and then slowly zig-zag down the other. They descend into the gorges, and they go over the mountain passes, and they get there eventually, but it’s always slow.

Notice the mapped routes of the G214 Guodao and the under-construction G0613 Expressway follow basically the same route - this is is not a coincidence. The two roads often follow the same basic natural geographic features through valleys, around mountains, etc. The main difference is the expressways will cover the same route in half the time or less, because they get to employ modern tunnels and flyover bridges. for the more extreme topography the Guodao always traverses the hard way.

The trade-off for taking the Guodao (besides being free of tolls) is they offer a much better view of the surrounding landscapes. This becomes very relevant in western China, where the Guodao offer some of the most gorgeous scenery possible that can be easily reached from a national trunk road. They’re also often crowded with slow-moving traffic, including RVs and large trucks avoiding toll roads, which makes it easier for me to take unsafe videos while driving. :)

Most of the Guodao aren’t particularly notable - they’re just transportation tools for getting from Point A to B. However, some are VERY famous for their breathtaking scenery and hold special lure for travel enthusiasts. There’s a major tourist sub-culture built around driving the Guodao, especially the ones traversing remote parts of Western China like Tibet, Sichuan, Qinghai, and Xinjiang. The one I’m driving north of Shangri-la - G214 - is not a major one, but it’s not a minor one either. I’d say it’s an averagely-famous one.

Some Guodao have achieved nigh-cult status for outdoor enthusiasts. Similar to tourist who seek to drive Route 66 or Route 1 in the USA, in China driving some of these Guodao IS the destination and goal. Or rather, if you drive that Guodao, you’ll surely see amazing things along the way - trip planning is made as simple as possible.

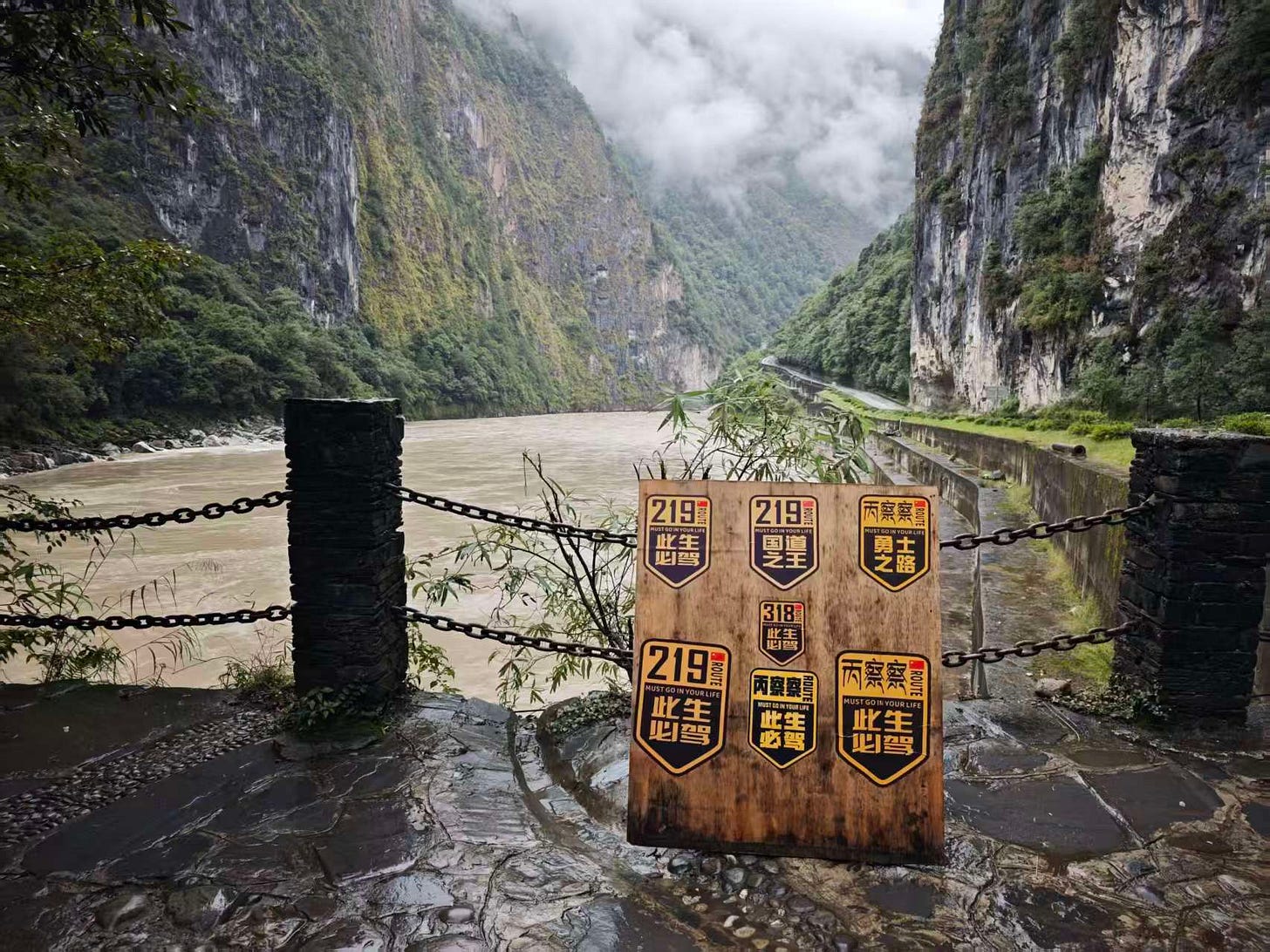

You’ll even see people even put stickers on their cars and RVs saying things like “此生必驾318国道”. “In this lifetime, I must drive National Highway 318” or 此生定情214国道” In this lifetime, my heart is fixed on National Highway 214”.

The most famous Guodao with the highest attraction value for overland travelers are:

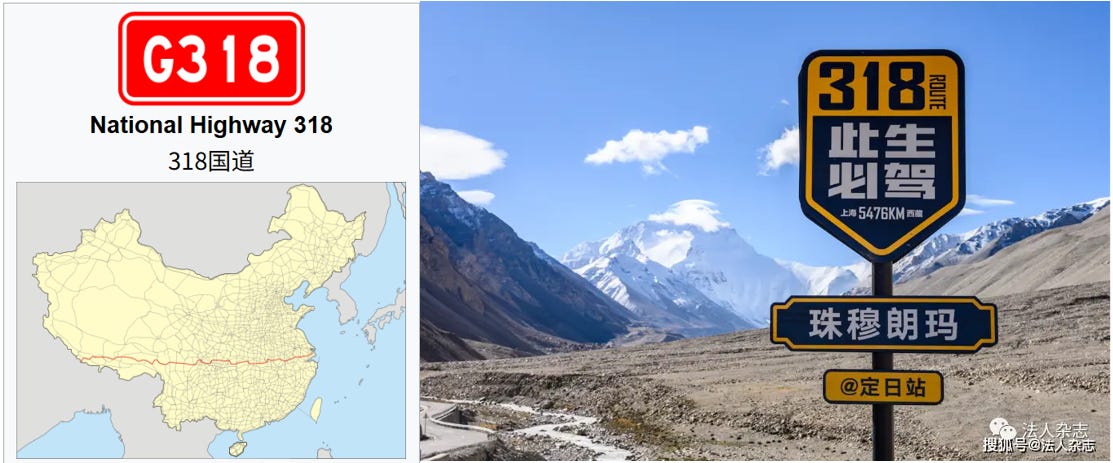

G318: The granddaddy sightseeing gem of the Guodao system, running 5476 km from Shanghai to Zhangmu near Mt. Everest on the Tibet-Nepal border. The most famous sightseeing portion starts in Western Sichuan. Honestly, the portion going through central China is probably pretty unremarkable, but the Sichuan-Tibet portion is one of the most famous sections of roadway in China and is driven every year by tens of thousands of sightseers.

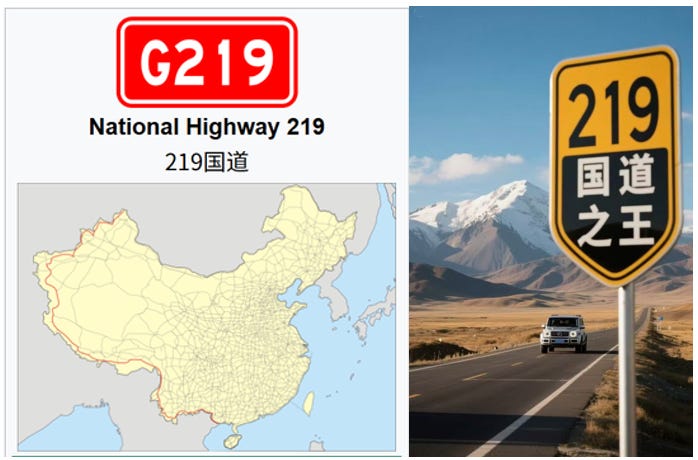

G219: Also called the Tibet-Xinjiang highway, the “Sky Road”, or 国道之王 “The King of Guodao”. It is billed as the worlds highest-altitude highway, with long sections exceeding 5000 meters and a high point at the Hongtu Daban pass at 5355 meters. Some parts are still under construction, but when finalized it will become the longest road in the Guodao system at 10000+ km. The shorter section passing through Yunnan that I drove later in the trip is called the “Bing Chacha” (丙察察).

G331: The current longest Guodao, following China’s northern border for over 9200 km from Dandong, Liaoning to Altay, Xinjiang. I’ve never been on this highway. It’s a favorite of overland RV travellers and usually takes several months to drive at a reasonably touristy pace.

G228: The coastal Guodao, which together with G219 and G318 allows a complete circumnavigation of China, over 27,000 km long. People on Xiaohongshu like discussing the feasibility of driving this entire loop route, how long it would realistically take to complete, etc.

Anyway, I don’t want to go through ALL of the famous Guodao. It’s enough for you, the reader, to know there’s a large and rapidly-growing adventurer “road warrior” culture in China, developing around driving them. People tour them in cars, RVs, motorcycles…even by bicycle (bikepacking).

The G214 north from Shangri-la is maybe not as famous as others, but still very pretty.

A major attraction heading north on G214 comes halfway between Shangri-la and Deqin County, just after Benzilan Town: the Great Bend of the Jinsha River 金沙江大湾. It has its own little rest stop area with a parking lot, coffee shop, ice cream, and viewing platform. Visiting is free, but parking will cost 10 CNY.

Here, the Jinsha River, after traveling roughly southeast down off the Tibetan Plateau for 1000+ km, rounds a huge bend in the topography and seemingly suddenly heads off due east. In reality, it resumes its southerly direction shortly thereafter, but you can’t see it from this viewing location. This viewing platform has become an important stopover milestone on the G214.

After the Benzilan Great Bend, the Jinsha River continues on its general southeasterly direction for a few hundred kms more, all the way until Lijiang, whereupon it undergoes another, more impactful Great Bend (Great Bend II: The Bendening). This Lijiang Big Bend actually sets it off in a new direction, heading northeast for the Sichuan border. After several more twists and turns, it merges with the Yalong River at Panzhihua before meeting the Min River in Yibin and becoming the mighty Yangtze.

If that second Great Bend doesn’t happen, the Jinsha River would perhaps instead end up merging with the Lancang River somewhere in central Yunnan instead. Maybe the ancient Chinese would have been made correct in their assessment that the Min River was the true headquarters of the Yangtze. Maybe the Yangtze wouldn’t exist at all. Southern China would be radically different. Would there still be a Wuhan, Nanjing, or Shanghai?

From the Benzilan Great Bend, we left behind the Jinsha River gorge and drove west via Baima Mountain (白马雪山). As I mentioned in a previous post, traveling north-south in this part of Yunnan is simple - following the river gorges - while traveling east-west is much more tedious, as it means crossing a mountain. Fortunately, this one isn’t too difficult and the G214 is in good shape though here.

After crossing the mountain pass, we descend into the valley gorge of the Lancang River instead, which runs almost parallel to the Jinsha River. This is the only way to reach the remote Deqin County, the northernmost point in Yunnan. Deqin is a majority Tibetan region in Yunnan and is the jumping-off point for touring Meili Xue Shan (mountain) 梅里雪山 and other points further north into Tibet.

Arriving in Deqin, G214 brings you first to Wunong Peak, which provides panoramic views of the Deqin County seat, as well as Meili Xue Shan to the north (shyly shrouded in clouds the day I arrived).

Deqin County itself is tucked between sheer cliffs, vulnerable to rockslides and landslides. After many years of debate, the provincial government has begun the difficult task of relocating the entire county town to a new location less vulnerable to geological risk. At this point, about half the town is empty, by my estimate. But the tourism sector is still active, based around Wunong Peak and Meili Xue Shan.

Deqin was small, with a population of just 70k even before the relocation started. There’s really only one main road running through town, declining at a constant 30 degree angle as it descends deeper into the Lancang river gorge. Deqin is jokingly called 一线城市, a hononym for “first-tier city” that can also mean “one-road city”.

Although it looks pretty from above, there’s very little to do in town - not even much in the way of restaurants or hotels. The real attraction is about 10km further up the gorge at the Feilai Temple town, visible in this shot across the valley. That’s where the best views are - and the G214 brings us there.

It takes 30 minutes to navigate the short 10km right to the town, thanks to the constantly winding road. Feilai Temple town is basically a village of a few hunrded people carved out of a cliffside and is now obviously straining under the weight of its growing tourism sector, with guesthouses and restaurants cascading up the hillside, all promising direct views of Meili Xue Shan - weather permitting of course.

Each morning before dawn, hundreds of tourists stream out of their guesthouses and hotels to line up at the viewing platform, facing east towards Meili Xue Shan, hoping to glimpse the elusive “golden sunrise” when the first rays of sunshine from the west illuminate the mountain with a striking golden crown. A row of white stupa provide the perfect framing for the shot - if you’re lucky enough to get it.

When it gets too crowded on the viewing platform, shops allow access to their rooftop balconies - in exchange for a 10 CNY purchase. Smoke from burning boughs at the nearby incense altar wreath the stupas. The vibes are perfect. Unfortunately, the clouds will not be denied. I stayed for two days and didn’t catch the golden sunrise - which is infamously shy - on either day. Supposedly, you’ve only got about a 10% shot of seeing it on any given day. Bummer.

Fortunately, there are other interesting things to do here. Mingyong village is about an hour’s drive north from Feilai Temple town, deep in the Lancang River gorge. This is the trailhead for the Mingyong Glacier hike. I’d never been to a glacier, so I was quite keen to check it out. I’ve seen the Lancang River before, where it passes placidly through Xishuangbanna, but this my first time to see it like this, angry, swift-moving, swollen and turbid from recent rains. It scratches out a deep valley hundreds of km long though this part of Yunnan.

Mingyong village was small - just a few dozen Tibetan houses. It surprised me its vineyards and advertisements for ice wine, of all things. I didn’t know Yunnan had a wine industry...

I got what I think is a pretty neat picture: grape vines and a glacier in the same picture (separated by 1000+ meters of elevation). I guess it’s not THAT rare (glacial soil is good for grapes and there are lots of vineyards close to mountains worldwide) but I didn’t expect to see it in Yunnan.

From the Mingyong Glacier trailhead, it’s a short ride on a touring vehicle partway up the mountain, but then it’s a hike. You have two options: the wooden plank stepway, or the dirt trail (shared with horses). I opted for the stairs.

After a brisk 90 minute hike up the moutain, I reached the top platform and got my first glimpse of a glacier - reasonably up close. Sadly, it was obvious the tip of the glacier had receded up the mountain several hundred meters vs pictures I had seen online from a just a decade ago. The bottom sections of ice were so stained so filthy with accumulated soil that I thought they were rocks at first.

But up higher, the dirty ice turns into white snow and ice, and it starts to look like something you’d actually want to walk on.

On the platform, a young guy was flying his drone much higher up on the glacier, panning over the misty walls of ice and snow. Suddenly he shouted it with excitement “there! there! it’s falling!”

His girlfriend rushed over and I peered over his shoulder too to look at the small screen, to watch a huge chunk of snow and ice the size of a small house separate from the ice wall and crash onto the jagged glacial floor far below, somewhere out of sight far above us.

After a few more pictures from the small temple at the top of the glacier hike, I made my way back down the mountain. This is a really nice hike, and it’s also possible to take a horse to the top as well if you aren’t feeling up to it otherwise. Highly recommended! Especially as the glacier is clearly disappearing.

BTW, previous mountaineering attempts on Meili Xue Shan had tried and failed to ascend via the Mingyong Glacier route. However, the ill-fated 1991 climb attempt which resulted in 17 deaths (by avalanche) in a Sino-Japanese joint mountaineering team used a different route. Climbing was banned thereafter and so Meili Xue Shan remains officially unsumitted today - a virgin peak at 6740 meters. You can read more about this tragedy here.

This video essay is getting long, so I’ll wrap it up here. Next time, I’ll share more about the rapidly-emptying Deqin County town which will soon be an ACTUAL ghost city, what people think about the relocation, and my exploration of Deqin’s Adunzi old quarter. Thanks for reading!

Really interesting part of the world. When I wrote a treatment for a proposed documentary series for Simon Reeve I included the Ao Yo vineyards of Shangri La - some of Chinas most expensive wine. Suffice to say the series isn’t going to be made- too difficult- too expensive- too politically problematic- shame as so little is known about ‘deep China ‘ in the UK. Keep on writing- there a book or two in you.